The Uncertain Effects of HTTPS Adoption on Access to Information Worldwide

by Casey Tilton

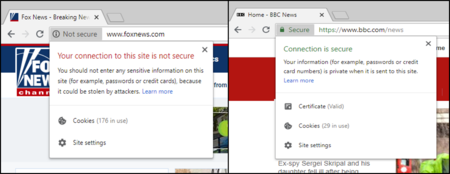

With the July 24 launch of Google Chrome’s latest version, Chrome 68, all unencrypted, “HTTP” websites are now marked as “Not secure.” In other words, all Chrome users will see a “Not secure” warning in the URL bar when they attempt to access sites that are not delivering content through HTTPS.

HTTP — hypertext transfer protocol — is one of the underlying protocols that allow communication between web browsers and the servers of websites. When users access sites through HTTP instead of HTTPS, they are at risk for having their online activity monitored by anyone with access to the wires, whether that be a hacker trying to steal credit card information, a government official monitoring a citizen’s browsing activity, or any other third party with nefarious intentions.

The solution to the unsecure nature of HTTP is HTTPS, an encrypted version of the protocol that makes it very difficult for third parties to spy on specific activity within a website. With HTTPS, data is scrambled when it is sent over the web and decoded after it reaches its intended destination. Because of the nature of the encrypted transmission, even if someone were to intercept the data, they wouldn’t be able to read it.

Although the positive consequences of HTTPS adoption in regards to online security and privacy have been well documented, the implications of this global trend on Internet filtering and access to information are mixed. During the days before HTTPS, government censors could block specific web pages within a domain. For example, before Wikipedia implemented HTTPS in 2015, governments could filter specific Wikipedia articles while allowing access to the vast majority of content on Wikipedia. HTTPS makes this type of fine-tuned filtering very difficult, which poses a challenge to government censors. Now that social media platforms and many news sites are encrypted, censors have a hard decision to make: do they block the entirety of popular platforms like Wikipedia, Facebook, or Medium because of a few offending articles or pages? Or do they allow all of the content to remain accessible?

This piece analyzes the extent to which the web is moving to HTTPS-only content delivery and reviews studies by Internet Monitor and others that suggest the trend could have uncertain long-term implications for online access to information around the world.

Increasing adoption of HTTPS

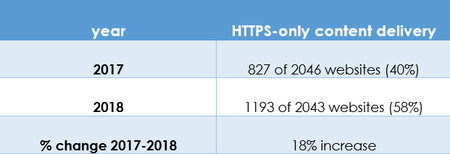

In a 2017 Internet Monitor study, we analyzed the extent to which the web’s most popular sites were starting to move to default HTTPS encryption. To do so, we attempted to access each of the urls on our global testing list through HTTP and HTTPS. The global testing list consists of the Alexa top 1000 sites plus 1043 additional websites that filtering experts deemed to be internationally relevant. The list includes the urls for international media organizations, social media platforms, human rights websites, commercial sites, pornography, gambling sites, dating sites, search engines, anonymizers, and more.

We found that as of June 2017, 40% of the sites on the global testing list had transitioned to HTTPS-only content delivery. HTTPS-only content delivery means that even if a user attempts to access an encrypted site through HTTP, the site will automatically redirect to an encrypted HTTPS connection. For example, users attempting to access Facebook by searching http://www.facebook.com are automatically redirected to https://www.facebook.com. Although many of the most popular sites including facebook.com, google.com, wikipedia.org, and amazon.com fell into this list, many others were still not enabled for HTTPS by default as of June 2017. Popular sites that had not made the transition to HTTPS-only delivery as of last June included slate.com, cnn.com, npr.org, and bbc.com/news.

In light of the Google Chrome upgrade, we tested the urls on our global testing list again in June 2018 to see how much progress has been made in the web’s adoption of HTTPS over the past year. We found that 1193 (58%) of the 2043 sites on the global testing list are encrypted by default, which is an 18% increase from June 2017.

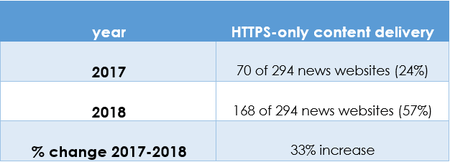

A 2017 study published in the Journal of Cyber Security Technology found that HTTPS adoption varies across industries and that it was strongest within the computer industries sector and weak within news and sports websites. Internet Monitor’s 2017 study revealed similar findings about the lack of HTTPS adoption among news websites: of the 294 sites categorized as news on our global testing list, only 70 (24% of 294) were encrypted by default in June 2017. However, the number had increased by 33% to 168 (57% of 294) a year later. Although the list of 294 news websites is not a completely representative sample of all news websites around the world, the substantial increase over the past year is noteworthy.

Despite the impending Chrome changes, there are still several popular sites that are not encrypted by default. The sites of Fox News, Los Angeles Times, Time, ESPN, and IGN, among others were all marked as “not secure” in Chrome as of the July 24 launch date.

We concluded in our 2017 analysis that HTTPS use was clearly on the rise but that HTTPS adoption still had a long way to go, even among the web’s most popular sites. One year later, it’s evident that both of the conclusions still hold true. Other researchers have performed analysis that support a similar conclusion. According to security researcher Scott Helme’s analysis of the Alexa Top 1 million, 38% of sites were redirecting to HTTPS in Feb. 2018, up from 31% in August 2017. Although this increase over a six-month span is noteworthy, Helme detected a slowdown in the rate of increase in HTTPS adoption between Aug. 2017 and Feb. 2018 compared to previous years. It remains to be seen whether future reports will show a similar slowdown in the adoption rate.

HTTPS and access to information around the world

Studies by Internet Monitor and others reveal that encryption has led to greater accessibility of popular platforms in some cases and to overblocking in others. An Internet Monitor report from April 2017 about censorship of Wikipedia suggested that Wikipedia’s move to HTTPS had a net positive effect on access to Wikipedia around the world. For example, the Iranian government has not blocked the entirety of Wikipedia since the platform transitioned to HTTPS in June 2015 despite the censors having blocked hundreds of specific Persian-language articles before 2015.

In other cases, the popularity of HTTPS-protected platforms has not stopped governments from cutting off access to an entire platform because of a few offending articles. Turkey blocked Wikipedia in April 2017 because, according to the Turkish Communications Ministry, the site contained information that suggested the country supported terror activity. In June 2017, Egypt blocked Medium.com, the preferred publishing space for authors to bypass blocking in the region, even though the vast majority of articles on Medium are unrelated to Egyptian politics.

Internet users behind censorship regimes have used HTTPS-encrypted platforms like Facebook or Google Drive to disseminate content that is otherwise blocked. For example, Egypt blocked the website of Human Rights Watch in Sept. 2017, one day after the organization released a report critical of Egypt’s policing practices, torture by security forces, and forced disappearance. In reaction to the censorship, Egyptian Twitter users widely shared links to a Google Drive account that hosted the banned report.

According to Internet Monitor research, it is becoming increasingly common for citizens in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region to use Google Drive to host the content of blocked websites. For example, the MENA-centric news website al-Araby al-Jadeed, which is blocked in Saudi Arabia, UAE, Egypt, and Yemen, cross-posts content on Google Plus and Google Drive.

It is difficult to estimate the long-term effects of HTTPS adoption on freedom of information worldwide. If the current popularity and ubiquity of social media platforms are any indication, the overall share of content hosted by centralized, encrypted social media and publishing platforms will likely continue to grow in the future. And if so, it will become increasingly difficult for a government to censor the content it deems objectionable while avoiding the collateral damage that comes with blocking entire platforms.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Justin Clark for testing the HTTPS connectivity status of the urls on the global testing list in 2017 and 2018 and to Gretchen Weber and Mary Meisenzahl for editorial feedback.

Casey Tilton is a Research Associate at the Berkman Klein Center where he researches Internet content controls and online activity for the Internet Monitor project.