The Slippery Slope of Internet Censorship in Egypt

The Slippery Slope of Internet Censorship in Egypt

In response to a recent, dramatic increase of Internet filtering in Egypt, Internet users take to social media and Google Drive to protest filtering and disseminate banned content.

Internet filtering in Egypt illustrates how censorship can be a slippery slope. After an extended period of open access to the Internet in Egypt lasting several years following the January 2011 revolution, the government dramatically increased its censorship of political content between December 2015 and September 2017. What started with the filtering of one regional news website in 2015 has led to the filtering of over 400 websites by October 2017. The blocked websites include local and regional news and human rights websites, websites based in or affiliated with Qatar, and websites of Internet privacy and circumvention tools.

This bulletin examines how Egyptian Internet users have reacted to the pervasive blocking and describes their efforts to counter the censorship. These efforts center on disseminating banned content through platforms protected by encrypted HTTPS connections such as Facebook and Google Drive, which makes individual objectionable URLs challenging for the censors to block.

There was no evidence of Internet filtering in Egypt following the January 2011 revolution, during which the regime of ousted president Hosni Mubarak blocked access to a number of websites before it shut down the Internet. Egypt’s government attempted to introduce filtering of objectionable social content such as sex websites in 2012,[0] but the efforts did not materialize. The censors reintroduced selective political filtering later. The first documented example was in December 2015 when the authorities blocked the news website al-Araby al-Jadeed.[0]

Starting in May 2017, the censors increased the number of blocked websites when national ISPs blocked 21 local and regional news websites, including local online news website Mada Masr and Al Jazeera, for allegedly supporting terrorism and spreading fake news.[0]

The censors have also blocked websites affiliated with the Muslim Brotherhood, which the government has declared a terrorist organization; websites of local media such as Elbadil.com; and websites of international media such as Huffington Post Arabic. Moreover, the censors have since begun to block websites of regional human rights groups such as the Cairo-based Arabic Network for Human Rights Information (ANHRI), and the international advocacy organization Reporters Without Borders (RSF).

The Egyptian government blocked access to the website of Human Rights Watch (HRW) on September 7, 2017, one day after the organization released a report critical of Egypt’s policing practices, torture by security forces, and forced disappearance.[0] Filtering of such prominent international human rights and advocacy websites is rare, even in some countries known for pervasive filtering of political content; only China and Iran are known to have blocked both RSF and HRW.[0]

In the course of the filtering campaign, the censors also blocked access to the entire publishing platform Medium.com, which has been used by authors to bypass Internet blocking of smaller independent websites.[0] As filtering of political content continues to expand, the censors have also blocked websites of hundreds of circumvention tools, which netizens can use to bypass the filtering regime and to surf the Internet anonymously.[0] By September 2017, the number of websites known to be blocked reached 432.[0]

Examining the conversation about filtering and how users react

We examine in this bulletin how users react to Internet filtering and if they attempt to bypass the technical filtering regime. Specifically, we examine the conversation about the blocking of websites in Egypt on Twitter, identify spikes in conversation volumes, and examine if users resort to alternative means to disseminate banned content.

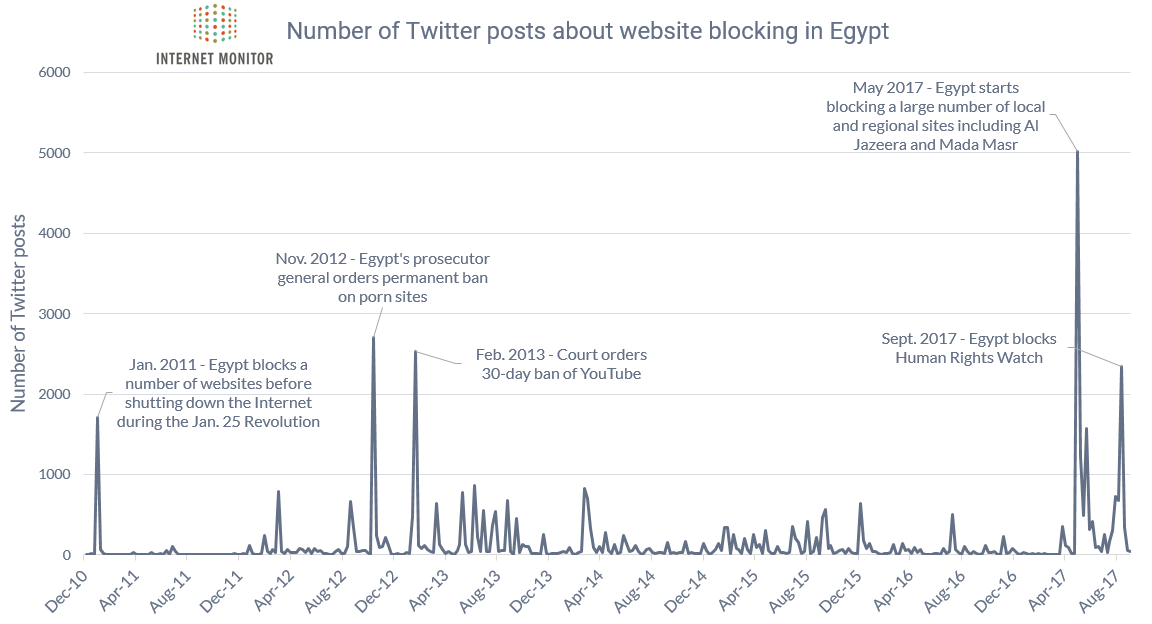

We used social media analytics platform Crimson Hexagon to uncover insights from social data and to monitor the conversation on Twitter between May 2008 and September 2017. We used the Arabic terms حجب موقع مصر (website blocking Egypt) to search the library of historical public tweets. The total number of tweets generated with this search query was 48,895.

The conversation about Internet filtering in Egypt on Twitter started during the January 2011 revolution. The first significant peak in conversation was during the popular uprisings during which the regime of ousted president Hosni Mubarak blocked a number of websites before it shut down the Internet.

Other peaks were between 2012 and 2013 in reaction to user campaigns to block pornographic websites and an order from the public prosecutor to block them, which had not been implemented. The highest peak in conversation was in May 2017 when the censors started blocking a large number of political websites, including local and regional websites and Qatar-based media over the diplomatic row with Qatar.[0]

The conversation reveals interesting observations about URLs shared by users between April and September 2017:

- The most frequently shared URL is a website that reposted the HRW report as an alternative to the blocked website.[0] We tested access to this website and found it to have been accessible since it was first widely advertised on Twitter.

- Also among the top 10 shared URLs is the HRW critical report reposted by users on Google Drive.[0] Google Drive requires user to connect through a secure HTTPS connection, which makes it challenging for the censors to block specific documents hosted on Google Drive without blocking Google Drive entirely. Using Google Drive to host banned content is becoming increasingly common in the region. For example, the news website al-Araby al-Jadeed, which is blocked in Saudi Arabia, UAE, Egypt, and Yemen, makes its content available on Google Plus and Google Drive.[0]

- In reaction to the blocking, users share more reports critical of human rights practices in Egypt. Examples of shared reports, which also appear among the top shared URLs, include reports from HRW,[0] Amnesty International,[0] and the regional advocacy group ANHRI.[0]

- Also in reaction to the blocking, the Facebook pages of the blocked websites are increasingly shared. One example is the Facebook page of human rights advocacy group ANHRI.[0]

- Users share information about how to bypass Internet filtering in Egypt. Among the top 20 shared URLs are links to free VPN services and circumvention tools such as Psiphon and Tor Browser.

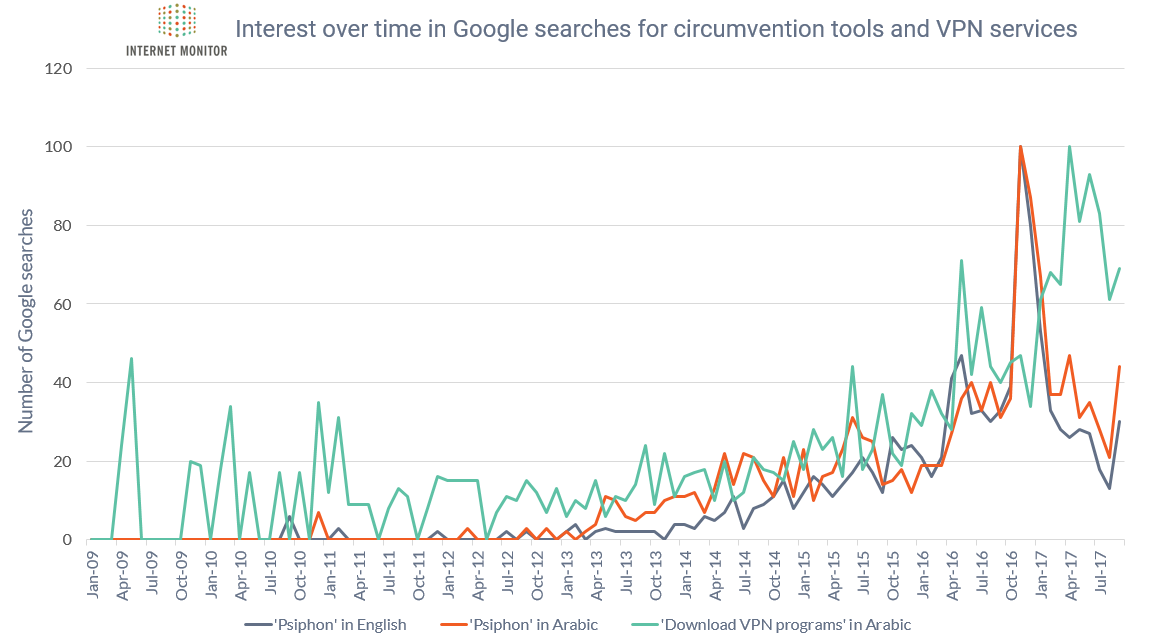

Using Google Trends, we examined if there has been any notable increase in searching for Internet circumvention tools in Egypt since the recent filtering wave began. We find that since the start of the selective political blocking in late 2015 there has been an increase in search queries for circumvention tools such as Psiphon and VPN services. We infer from the Google Trends data that there has been an aggregate increase in demand for circumvention and privacy tools to bypass the technical filtering regime and to surf the Internet anonymously. We cannot determine the proportion of this demand that is due to blocking of websites in Egypt, but the correlation is noteworthy.

Discussion

The recent wave of political Internet filtering in Egypt started with selective filtering of a few websites but progressed to pervasive blocking within 20 months. Internet censorship in Egypt illustrates how censorship can be a slippery slope both in quantity and significance of blocked content. The censors started with a few local news portals but quickly reached key local advocacy organizations. Later they hit international human rights groups and advocacy organizations such as Reporters Without Borders and Human Rights Watch. Meanwhile, the censors have been blocking hundreds of privacy and circumvention tools, which indicates a determination to prevent users’ attempts to bypass the filtering regime.

State Internet censors are able to block access to entire websites, and some take the aggressive measure of blocking entire publishing platforms, such as the case with Medium.com in Egypt. However, information control in the social media age can be challenging, even for governments like Egypt that pervasively filter political content. Users take to social media not only to discuss and protest filtering but also to disseminate and publicize alternative ways to access blocked content. The fact that the top shared URL on Twitter is a website that reposts the Human Rights Watch critical report is noteworthy. Moreover, the dissemination of blocked content on services such as Google Drive poses a significant challenge to the authorities. This leaves the authorities with limited and tough options: allow all content or block all content.

References

- Al-Masry Al-Youm, Blocking internet pornography a priority for telecom minister, Egypt Independent, 22 March 2012

- ANHRI Denounces Blocking Al-Araby Al-Jadeed Website, ANHRI, 31 December 2015

- Ahmed Aboulenein, Egypt blocks 21 websites for 'terrorism' and 'fake news', REUTERS, 24 May 2017

- Egypt Blocks Human Rights Watch Website, Human Rights Watch, 7 September 2017

- The Shifting Landscape of Global Internet Censorship, Berkman Klein Center, 29 June 2017

- The Shifting Landscape of Global Internet Censorship, Berkman Klein Center, 29 June 2017

- Decision from an Unknown Body: On blocking websites in Egypt, AFTE, 4 June 2017

- Decision from an Unknown Body: On blocking websites in Egypt, AFTE, 4 June 2017

- The Shifting Landscape of Global Internet Censorship, Berkman Klein Center, 29 June 2017

- Full text of Human Rights Watch report: "Egypt: A Pandemic of Torture May Be a Crime Against Humanity" after blocking its location in Egypt, MENA Rights Cable

- https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B7J7koHeJLiiZWdGQUx0STZBTG8

- Al Aaraby News on Google Plus

- Egypt: Intensifying Repression of Basic Freedoms, Human Rights Watch, 15 June 2017

- Dozens of news sites blocked as Egypt ramps up digital censorship, Amnesty International, 13 June 2017

- Egypt Prison Walls Become Too High: More than 21 Websites Blocked, ANHRI, 25 May 2017

- ANHRI on Facebook

Contacts

Contact Casey Tilton or Rob Faris with any questions.

Research Bulletins

- Internet Censorship and the Intraregional Geopolitical Conflicts in the Middle East and North Africa

- Censorship and Collateral Damage: Analyzing the Telegram Ban in Iran

- The Yemen War Online: Propagation of Censored Content on Twitter

- Iran's National Information Network: Faster Speeds, but at What Cost?

- The Slippery Slope of Internet Censorship in Egypt