Censorship and Collateral Damage: Analyzing the Telegram Ban in Iran

Censorship and Collateral Damage: Analyzing the Telegram Ban in Iran

In an attempt to stay connected to Iran’s most popular social messaging application, Telegram, after it was blocked in Iran in April 2018, Iranian Internet users adopted Psiphon and other circumvention tools in unprecedented numbers. The Iranian government responded in turn by attempting to block access to the circumvention tools, which led to pervasive network interference across the country.

by Simin Kargar and Keith McManamen

Abstract

In late April 2018, Iran’s Judiciary announced a much anticipated ban on the popular messaging application, Telegram. The filtering order instructed all Internet Service Providers (ISPs) in Iran and the Telecommunications Ministry to block access to content on the Telegram network.[0] The ban went into effect despite the record breaking popularity of Telegram, which was used by an estimated 40 million Iranians.[0]

Iranian users rushed to apply circumvention tools to stay connected to Telegram despite the concerted efforts of different political bodies to diminish attention to the app. Much of the state’s effort centered on migrating Telegram users to domestically developed alternatives. However, users expressed serious concerns about the security of state-sanctioned applications, and considered them to be facilitating state surveillance.

This research bulletin analyzes the aftermath of the Telegram ban in Iran and presents detailed data on the performance of Psiphon, one of the most widely used circumvention tools among Iranians. The bulletin concludes by reviewing the overarching Internet policies in Iran behind the Telegram ban. In addition, it presents the challenges that arise from the implementation of these policies, both to users and circumvention tool providers, especially as increasingly aggressive network interference becomes the norm.

Background

This filtering strategy immediately resulted in collateral damage to a much bigger audience than intended.

Since its launch in 2013, Telegram had become the top source of uncensored information in Iran. Its impact was so significant that it replaced many functions of the Internet, including email, messaging, discussion forums, blogs, news websites, e-commerce, social networks, and even television.[0] The political contention over Telegram, however, dates back to 2016 when reformists leveraged the messaging application in a parliamentary election to transform the way political campaigns were run. As a result, reformists won the majority of parliamentary seats against conservatives.[0] Similarly, Telegram played a key role in 2017 during the presidential election, which led to re-election of the moderate president Hassan Rouhani. During the protests that swept across Iran in late December 2017, Telegram was widely used to mobilize the protesters, with some Telegram channels encouraging violence and vandalism. In reaction to these escalations, the app was temporarily blocked. The ban was lifted once the protests subsided.[0]

The latest blocking that was announced in late April 2018, however, seems to be permanent. It is designed to encourage migration of Telegram users to domestic, state-endorsed alternative platforms. In an effort to obstruct access to tools that typically enabled bypassing of censorship, circumvention tools were heavily disrupted as well. But this filtering strategy immediately resulted in collateral damage to a much bigger audience than intended.

The Telegram Ban Goes into Effect

Shortly after the ban was announced, Telegram was removed from Cafe Bazaar, an Iranian online app store akin to Google Play (Figure 1).[0]

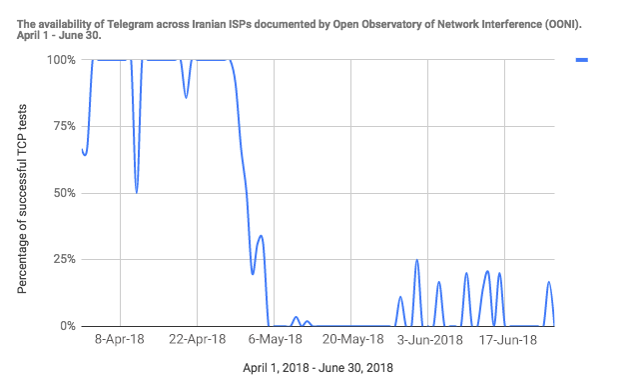

According to data collected by the Open Observatory of Network Interference (OONI), the blocking of Telegram began April 30. The blocking then turned into a consistent pattern on different ISPs by May 6. While Telegram has generally remained blocked since, individual tests indicating the accessibility of Telegram in June may suggest occasional errors in the Iranian censorship apparatus that lead to momentary unblocking of the application (Figure 2).

This was not Iran’s first attempt to curb access to Telegram. Concerns about Telegram intensified when it became a key organizing tool during the unrest that broke out across Iran in December 2017. As a result, a temporary ban on Telegram and Instagram went into effect for two weeks. The ban was later lifted as the protests subsided.[0] However, the current ban on Telegram differs from the first instance in two key ways. One, this decision was telegraphed in advance, as early as March 2018, whereas the first blocking event in December 2017 was abrupt as a reaction to the developments on the ground. Two, the court order in support of the more recent ban mandated that Telegram must be blocked in such a way that Iranians cannot access it by Virtual Private Networks (VPNs) or any other means.[0]

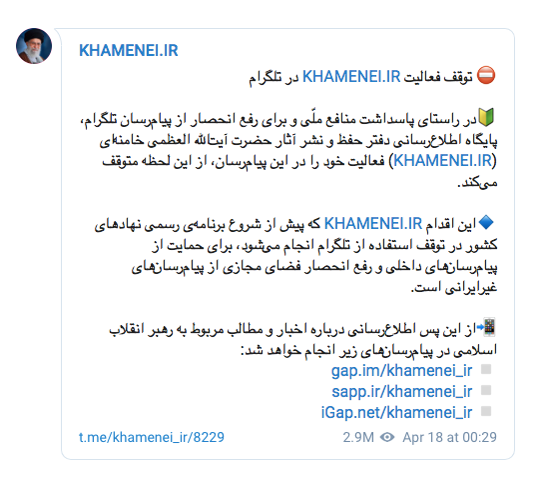

Ahead of the judiciary order, Iran’s Supreme Cyberspace Council (SCC) ordered that Telegram be removed from Iran’s Content Distribution Networks (CDNs), thereby slowing the transfer of multimedia data over the platform.[0] Furthermore, the office of Iran’s Supreme Leader announced that Khamenei’s Telegram channel was shutting down (Figure 3).[0] The shutdown was reportedly intended to safeguard national interests, to end Telegram’s monopoly on Iran’s social media, and to support domestic applications. For Telegram users in Iran, this signaled that a ban on Telegram was forthcoming.[0] Khamenei’s followers were encouraged to continue to follow him on Soroush, a homebrewed messaging app sponsored by the state.

In a separate executive order, the head of Information Security Center of the government prohibited all government bureaus and public institutions from using foreign messaging applications for official business.[0]

Public Reaction

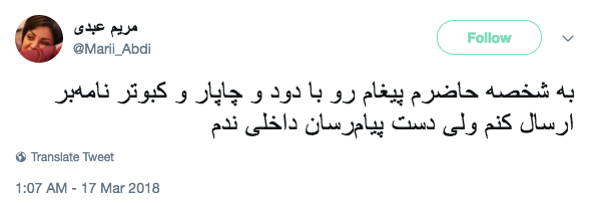

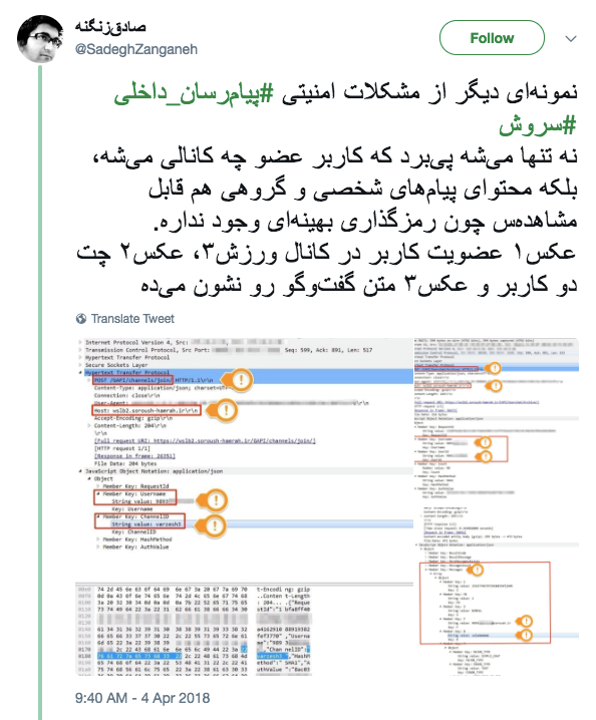

The ban on Telegram did not stop Iranians from using Telegram. Instead the ban was met with fierce opposition. Many resorted to circumvention tools to continue using the platform. Some expressed their lack of trust in state-sanctioned apps[0] and viewed them as tools that facilitate state surveillance (Figure 4).[0] [0]

Concerns about State-Sanctioned Applications

Many Iranian users resorted to humor in reaction to the state’s push to expand the user base of the Soroush messaging application as the main alternative to Telegram. One meme inspired by the movie Dictator shows Soroush as the winner of an unfair competition in which he enjoys special treatment and advantages in order to brutally defeat others.[0]

Many expressed criticism about their lack of trust in domestic apps due to what they suspect is state surveillance (Figure 4). They vowed to use proxies to continue using Telegram.

Some users raised concerns about the security threats that state-endorsed apps like Soroush posed to users. They argued that the Soroush backend discloses the identity of channel members and reveals the content of private and group messages due to the lack of encrypted messaging capabilities (Figure 5).

Resorting to Alternatives to Telegram and Circumvention Tools

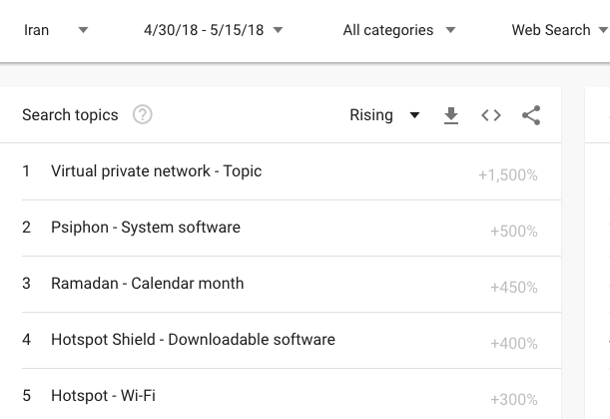

Google Trends search results from Iran between April 30 and May 15 indicate that four of the top five search topics were related to tools that could be used to get around the Telegram ban, including VPNs and circumvention tools such as Lantern, Psiphon, and Hotspot Shield (Figure 6).

Similarly, top search terms were often related to alternatives for Telegram such as Golden Telegram and TelegramDR. Golden Telegram was later found to be an insecure copy of Telegram with possible backdoors that could facilitate monitoring and manipulation of users’ data.[0] TelegramDR was developed in collaboration with Telegram with Psiphon as its built-in proxy tool.[0] The fact that both were among the top search queries confirms Iranian Internet users’ desire to stay connected to Telegram. For some users, the desire to remain connected meant downloading potentially unsafe tools without realizing that it left them vulnerable (Figure 7).

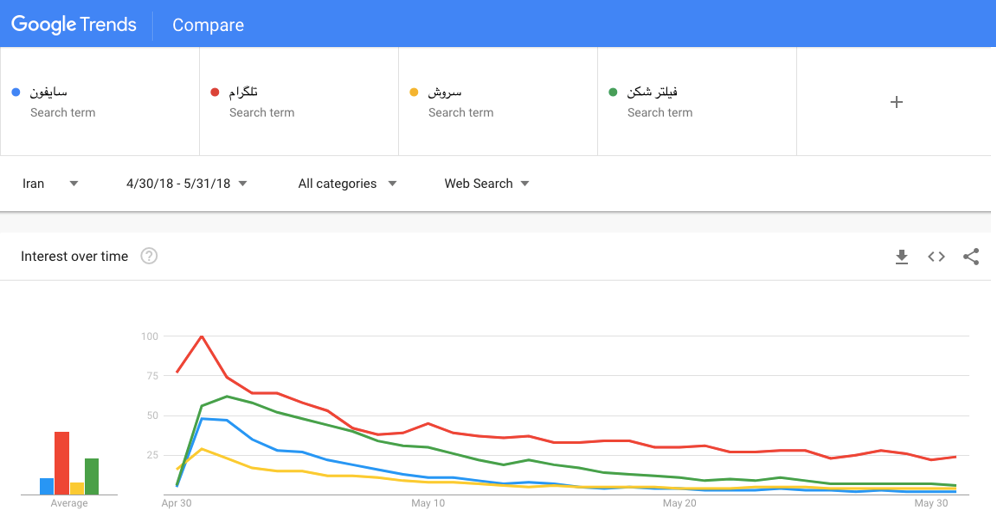

A comparison of select Persian search terms on Google Trends confirms that “Telegram” was the most queried term followed by “circumvention tool”, “Psiphon” and “Soroush” between April 30 and May 31 (Figure 8).

The sudden surge in search results on Google Trends for “Telegram” in English and Persian that occurred following the ban is noteworthy as they represent unprecedented peaks of interest in the past five years (Figure 9).

Blocking of Circumvention Tools

Two weeks after the Telegram ban went into effect, Iran’s Ministry of Information and Communication Technology (ICT) began to disrupt access to circumvention tools.[0] These were the very solutions that enabled Iranians to bypass the ban and access blocked applications or websites, including Telegram.

With 40 million Telegram and 24 million Instagram users in Iran affected by the sudden escalation in censorship, the blocking event drove unprecedented adoption of Psiphon on all platforms – Android, Windows, and iOS.

However, the move caused much more extensive disruption to Internet traffic in Iran. The Center for Human Rights in Iran documented that the Ministry of ICT was in effect blocking key elements of international Internet infrastructure, such as international data centers, web hosting, and cloud services, apparently because these are used by circumvention tools.[0] This resulted in pervasive collateral damage, disrupting domestic businesses, services, or websites that used the same infrastructure. The authorities also targeted encrypted international traffic used not only by circumvention tools but also by a broad range of Internet services and platforms. Internet users reported that speed and performance on Iranian networks overall were severely degraded and that numerous other websites, applications, and online services were affected by the blocking. In response to these pervasive interruptions, 100 Iranian IT experts and entrepreneurs wrote a letter to President Rouhani addressing the collateral damage caused by the decision.[0]

Surge in Psiphon Network Usage

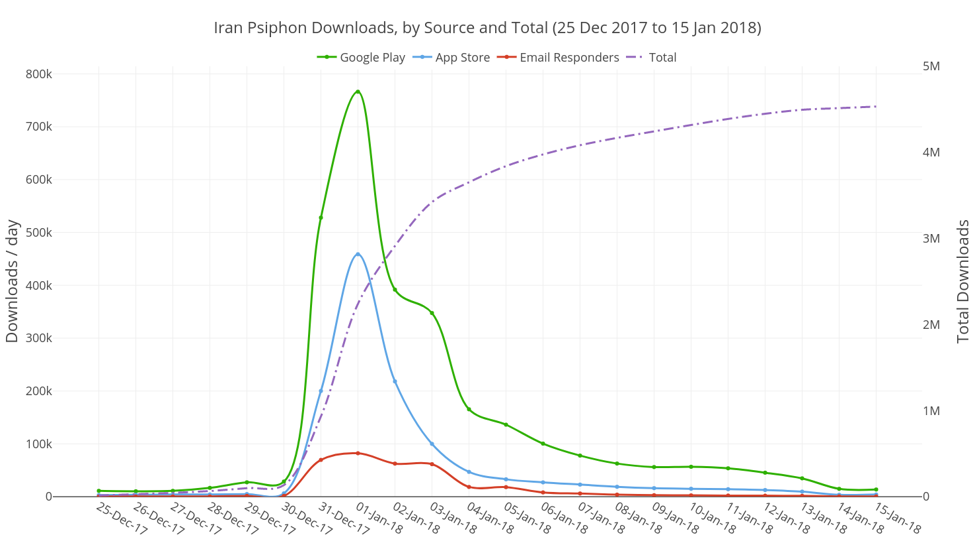

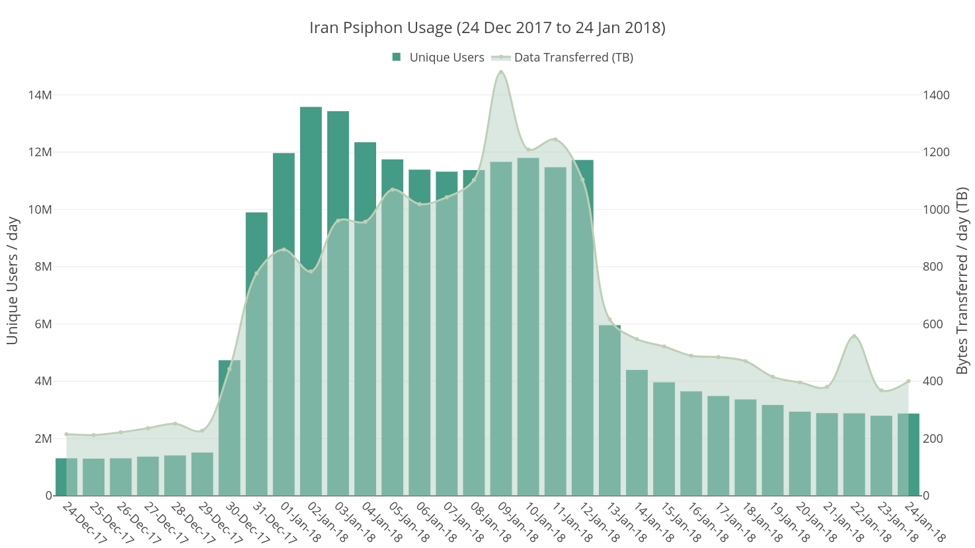

The blocking of Telegram and Instagram in late 2017 and early 2018 brought about a surge in the use of circumvention tools. These sudden blocking decisions swiftly drove unprecedented circumvention tool adoption throughout Iran as people rushed to restore their access to these popular platforms.[0]

For Iranians circumventing Iran’s filtering apparatus, Psiphon’s network has been a popular recourse since its inception in 2006. With 40 million Telegram and 24 million Instagram users[0] in Iran affected by the sudden escalation in censorship and reported capacity issues or network interference disrupting other leading circumvention tools, the blocking event drove unprecedented adoption of Psiphon on all platforms – Android, Windows, and iOS (Figure 10). Within days, Psiphon surged to a 10-fold baseline usage in Iran, reaching a peak of 14 million daily users, representing a remarkable ⅓ of Internet users in the country (Figure 11). Given that we only have usage statistics for Psiphon and that it is just one of several circumvention tools in use, the overall rate of circumvention tool usage in Iran is estimated to be considerably higher.[0] This broad-scale adoption of circumvention tools weakens the intended effects of blocking orders.

Psiphon’s Performance Under the Recent Telegram Ban

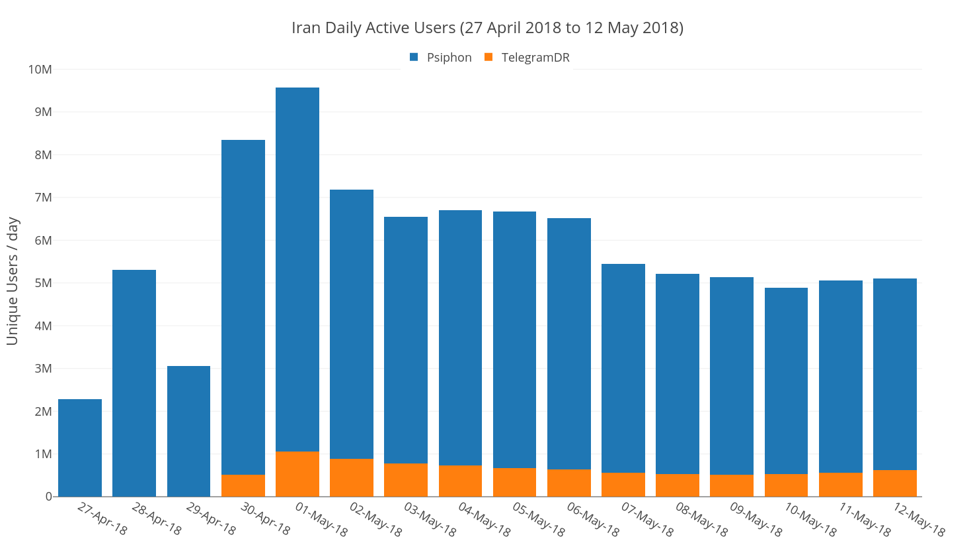

Many Iranians were prepared to circumvent Telegram because of the wide public anticipation of the blocking. Eight million Iranians were using Psiphon on May 1 after the ISPs began blocking Telegram the night of April 30 (Figure 12). The same day, a further one million Iranians also downloaded the new TelegramDR app, a censorship-resistant Telegram client utilizing the Psiphon library to tunnel all traffic from the application over the Psiphon network.

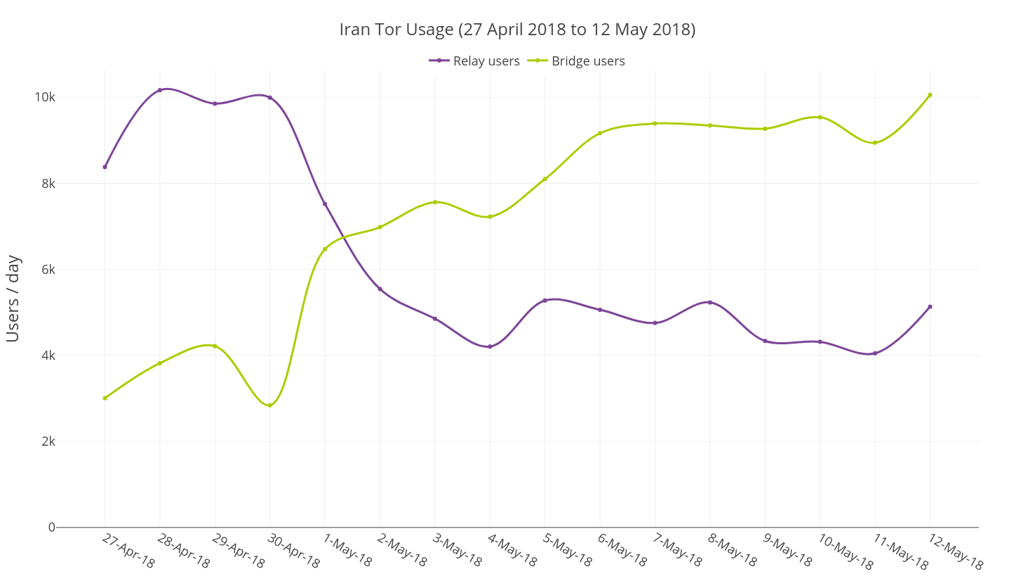

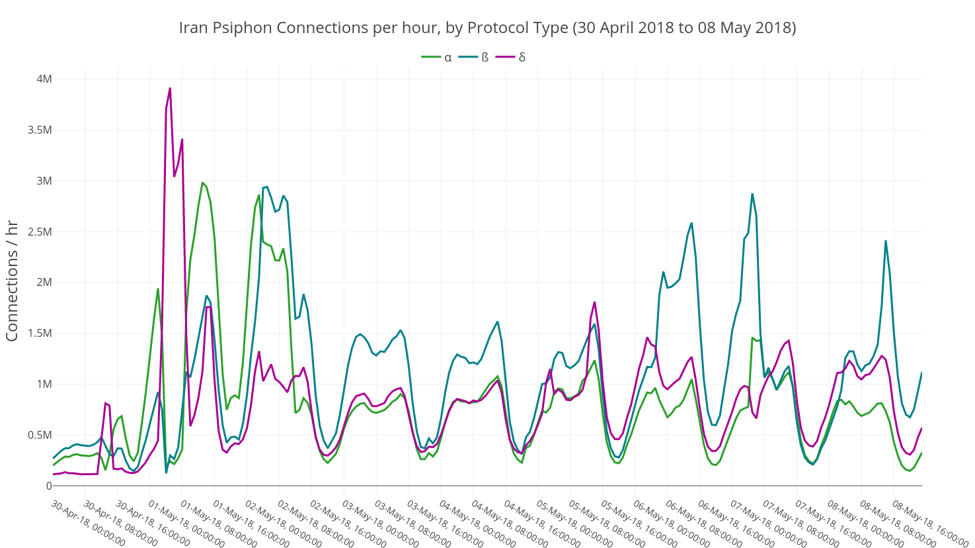

During the early days of the ban, Iranian censors began sweeping interference against general web traffic on networks across the country. Reports from inside Iran identified that many of the common transport protocols (methods of sending traffic over the Internet) used by generic VPN and proxy technologies and direct connections to the Tor network were blocked or had very poor performance.[0] Iran started blocking Tor on May 1, and Iranian Tor usage switched from direct connections to bridges (Figure 13). In addition, preliminary attempts were made to disrupt the Psiphon network via attacking specific protocols, although Psiphon through its use of multiple transports is resilient to this type of blocking (Figure 14).

Figure 14 visualizes some early disturbances in the normal Psiphon protocol distribution. Despite this attempted interference, during this time Psiphon continued working normally in Iran due to redundancy in its transport architecture. Using a diversity of transports provides the network with resilience to blocking on the basis of one or few protocols. Later, various Iranian ISPs deployed more advanced and specific filtering measures targeting Psiphon traffic.

Censorship circumvention on this large scale challenges the censors to either allow unidentified traffic to pass or to implement broad blocking that impacts general web traffic and interferes with core general-purpose Internet infrastructure. Psiphon is designed to be resilient even against attacks that specifically target its network. It resists traffic fingerprinting that can be applied using Deep Packet Inspection (DPI) technology, which can be effective against VPNs and other encrypted protocols. Through obfuscation and otherwise disguising traffic sent over the network, Psiphon is able to blend in with ordinary web traffic by making it indistinguishable from other general Internet traffic.

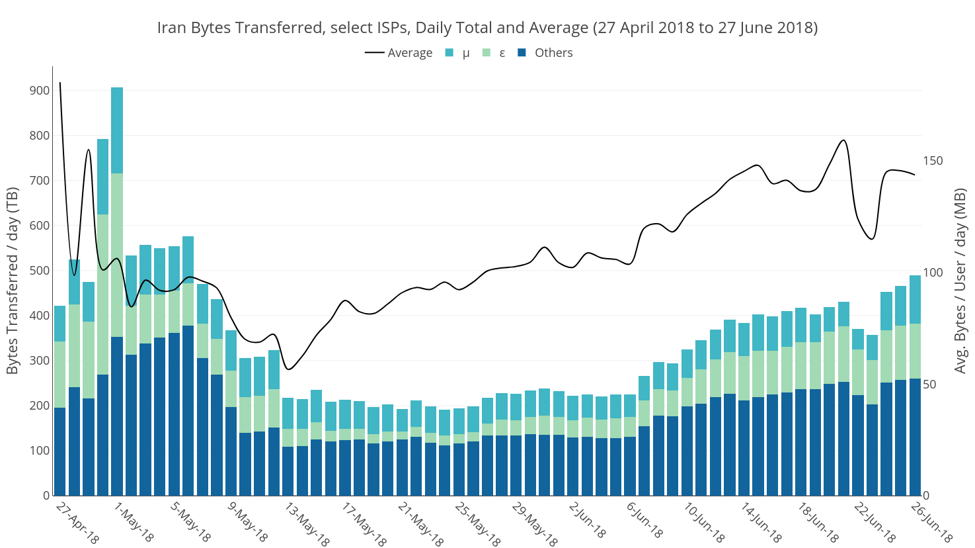

Through June 2018, 3.5 million Iranians access the open Internet via the Psiphon network on a daily basis, a 60% increase from the pre-ban baseline of 2.2 million daily users.

Psiphon traffic is potentially fingerprintable if censors are willing and capable of processing and analyzing enough data both longitudinally and in real-time. However, in attempting to block obfuscated traffic in many ways indistinct from general web traffic, the censors risk causing collateral damage to regular Internet usage.

As expected, given the compelling political motivation for enhanced filtering measures, collateral damage did occur. Starting May 14, Iran began filtering common Transport Layer Security (TLS) handshake protocols in an effort to block Psiphon traffic; Psiphon emulates common TLS profiles to blend in with ordinary web traffic.[0] The TLS handshake of Google Chrome, the most widely adopted web browser in Iran, was among those blocked. While this initially disrupted some Psiphon connections, unlike web browsers Psiphon can fail over to numerous other TLS profiles. Soon after, Iranian Internet users reported disruptions or poor performance on Chrome, Chrome Android, and a wide range of other Internet services.[0]

This demonstrates, once again, that censorship is often a blunt instrument that disproportionately impacts regular Internet users exchanging regular traffic. ‘Off-the-shelf’ commercial VPNs have relatively distinct signatures on a network level. However, more robust circumvention technologies like Psiphon are often able to resist fingerprinting attempts and targeted blocking by the censors due to the ever-changing nature of their network traffic.

While Psiphon continued to keep millions of Iranians connected to Telegram and the open Internet, the enhanced censorship measures deployed against the network in May affected the performance of Psiphon in two ways. One, the new filtering rules made it more difficult to establish a connection initially. While the majority of users still connected in under 10 seconds, connections taking 1-3 minutes to establish became much more prevalent, and on some ISPs connection times of up to 5 minutes were not uncommon. Secondly, bandwidth usage decreased both in aggregate and on a per user average (Figure 15). This was despite significant throughput – an average of 350 TB per day – being transferred successfully under the greatly deteriorated network conditions during the past two months.

The experience of the average Psiphon user varied, with some affected differently based on their ISP, platform, and version of the software, while others were not significantly impacted. For many Psiphon users in Iran, Psiphon continued to work normally with minimal interruption. Others resorted to an array of other circumvention tools at their disposal (Figures 6 and 7). Through June 2018, 3.5 million Iranians access the open Internet via the Psiphon network on a daily basis, a 60% increase from the pre-ban baseline of 2.2 million daily users.

Attention to Domestic Apps

Despite Iran’s orchestrated efforts, the popularity of domestically developed messaging applications has not grown as rapidly as Iran may have anticipated. With over five million active installs on Cafe Bazaar, Soroush has been the most popular domestic application among its intended audience.[0] It has grown from 100,000 installs on Google Play by the end of March 2018 to over a million by August 2018. [0] [0] However, these figures can hardly compete with the tens of millions of Telegram users (Figure 16).

Other domestic messaging apps such as iGap[0] and Wispi[0] have remained far behind Soroush and their international peers in terms of usage and downloads. In a meeting with parliamentary committees on national security, economy and industries on May 28, Iran’s ICT minister estimated that domestic messaging applications have attracted a total of seven million installs[0] and 10.5 million active users[0] thus far. He further estimated that only 1 million users had removed Telegram as a result of the blocking event.

Aftermath of the Telegram Ban

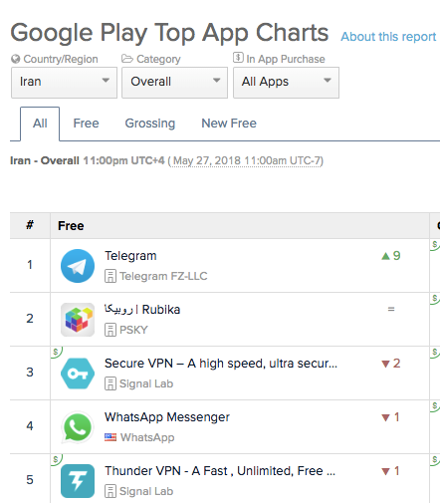

Telegram became the top used app in Iran again on May 27, several weeks after it was officially blocked.[0] According to App Annie data, two out of the top five apps in Iran on May 27 were messaging applications (Telegram and WhatsApp) and two others were VPNs (Secure VPN and Thunder VPN) that could be used to access Telegram and other blocked platforms (Figure 16).

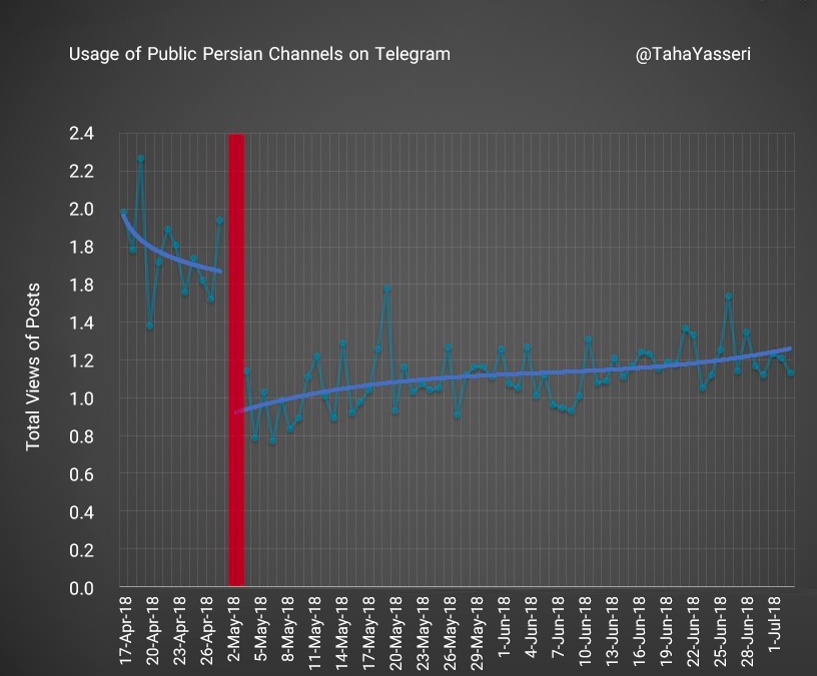

Two months after the ban, Telegram usage was down only by 30%, despite the ongoing blocking measures. Taha Yasseri of University of Oxford documented a gradual recovery in the usage of Telegram as the ban continues (Figure 17).[0]

Conclusion

The blocking of Telegram affected more than 40 million users on different levels of their personal, professional, and even financial lives. The enhanced censorship implemented in Iran following the Telegram ban therefore sheds light on several key lessons. First, it underscores that the determination to control information remains strong in Iran, even as President Rouhani and other leading elected officials expressed disapproval of the ban.[0] Such determination has led to prioritizing the blocking of international gateways at the cost of extensive collateral damage that affects the quality of communication at a national level.

The strategy of blocking international Internet infrastructure has not substantially scaled the user base of domestic alternatives to Telegram thus far.

Second, the blocking event highlights that the technical and human resources of the censors greatly exceed those of individual circumvention tools. This has resulted from longstanding interest and investment in a domestic Internet infrastructure. The National Information Network (NIN) has enabled the state to disconnect Iranians from the global Internet without substantially affecting domestic connectivity. This development can play a significant role in curbing freedom of information and expression, in particular at politically sensitive times such as the January 2018 protests. Iran has been incentivizing users to adopt the NIN’s state-controlled services, including domestic messaging applications, in exchange for faster speed and lower cost. The Telegram ban corresponds to this strategy fairly well.

Continued blocking of popular platforms coupled with the incentives offered for adopting state-controlled services may eventually drive more users to the NIN and its services (i.e. domestic traffic and platforms). This has significant implications for the privacy and security of users who adopt the state-monitored network and tools. While available stats indicate that many will likely continue to access Telegram through circumvention tools, the ban will still affect those with limited financial and technological capabilities. Network interferences often deeply affect users with lower bandwidth. This is the demographic who needs most support to adopt circumvention tools and may struggle to afford more expensive bandwidth subscriptions that can connect them to the global Internet.

Lastly, the Telegram ban may not have been entirely successful due to the extent of integration of the app in the lives of 40 million Iranians. Even resorting to the ambitious and unrealistic strategy of blocking international Internet infrastructure has not substantially scaled the user base of domestic alternatives to Telegram thus far. Yet the ban and Iran’s broader efforts to promote a state-controlled network represent the extent of political will to violate the rights to privacy, access to information, and freedom of speech. The ban also reveals that the intensified censorship was not sustainable indefinitely – it has political and social backlash, it is expensive, too imprecise in terms of targeting, and not completely effective.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Rob Faris, Mary Meisenzhal, Helmi Noman, and Casey Tilton for their editorial feedback and OONI for providing data on the blocking of Telegram.

References

- "دستور قضایی در خصوص مسدودسازی پیام رسان تلگرام صادر شد" [A judicial order was issued regarding the blocking of Telegram]. Mizan Online, April 18, 2018. Archived at https://perma.cc/S9FR-7DS7.

- Vahdat, Amir. “Iran orders Internet providers to block Telegram” Associated Press, April 30, 2018. Archived at https://perma.cc/SN67-K2JM.

- Derakhshan, Hossein. “Iran Lives on This App” New York Times, April 15, 2018.

- Miller, Christopher. “Messaging App Telegram is shaking up Iran's elections” Mashable, Feb. 25, 2016. Archived at https://perma.cc/UTT9-PGZA.

- Durov, Pavel. Tweet, Dec. 31, 2017. https://twitter.com/durov/status/947441456238735360. Archived at https://perma.cc/YP2A-ZWZV.

- Hafezi, Parisa. “Iran's judiciary bans use of Telegram messaging app: state TV” Reuters, April 30, 2018. Archived at https://perma.cc/7GXA-635N.

- “Iran unblocks Telegram messenger service shut down during country-wide protests” DW, January 14, 2018. Archived at https://perma.cc/N3QT-M8F3.

- “دستور قضایی مسدودسازی تلگرام صادر شد” [The judicial order was issued for blocking the telegram]. Fars News Agency. Archived at https://perma.cc/7N6W-6BBG.

- "کاهش کیفیت تلگرام با خروج سرورها از .زیرساخت” [Reduce the quality of the telegram by leaving servers out of the Infrastructure]. Iranian Students’ News Agency. Archived at https://perma.cc/C7PX-2CSK.

- Khamenei.IR. [ Stop KHAMENEI.IR activity in Telegram

In order to preserve national interests and to remove monopoly from telegram messengers, the information base of the Office for the Preservation and Publication of the Works of the Grand Ayatullah Khamenei (KHAMENEI.IR) in this messenger will be stopped from this moment.

KHAMENEI.IR This action, which is a non-Iranian messenger before the launch of a program that officially serves the country's institutions to stop using telegrams to support domestic messengers and eliminate cybersecurity.

From now on, information about the news and articles related to the leader of the Islamic Revolution will be made in the following messages:

▫️ gap.im/khamenei_ir

▫️ sapp.ir/khamenei_ir]. Telegram Message. Archived at https://perma.cc/4PZV-LR9W. - Dehghan, Saeed Kamali and Andrew Roth. “Ayatollah leaves Telegram as Iran prepares to block messaging service” The Guardian, April 18, 2018. Archived at https://perma.cc/FQ5G-7BWN.

- Iranidoost, Kamal. “Govt. offices banned from using foreign social messaging services” Mehr News Agency, April 18, 2018. Archived at https://perma.cc/55DW-VY8D.

- مریم عبدی, (Marii_Abdi). “به شخصه حاضرم پیغام رو با دود و چاپار و کبوتر نامهبر ارسال کنم ولی دست پیامرسان داخلی ندم” [Personally am willing to message with smoke and I send letters and pigeons chapar on hand, but the internal Messenger ndem]. March 17, 2018. 4:07 A.M. Tweet. Archived at https://perma.cc/PVS7-QPMZ.

- Esfandiari, Golnaz. “Some Bristle at Iran’s Offer of Unfiltered Internet to a Select Few” Radio Free Europe, April 10, 2018. Archived at https://perma.cc/25UT-9HJM.

- Sadegh Zanganeh. Tweet, April 4, 2018. https://twitter.com/SadeghZanganeh/status/981572285206167552. Archived at https://perma.cc/R5BW-Y8VQ.

- Farbod Ghotbi (FarbodGhotbi). May 1, 2018. 3:09 P.M. Tweet. https://twitter.com/FarbodGhotbi/status/991394174409863169 Archived at https://perma.cc/8E64-MJTM.

- Shahinzadeh, Yasar. “An Analytical Report Review the Security and Privacy of the Golden Telegram” Archived at https://perma.cc/85PN-XWDT. Golden Telegram was eventually removed from Google Play after multiple reports flagged it for security threats. See tweet by Nariman Gharib, an Iranian security researcher at https://twitter.com/NarimanGharib/status/1020611431337807872.

- TelegramDR’s website (https://telegramdr.com/) is currently blocked in Iran.

- “Iranian Starts Blocking Internet Filtering Circumvention Tools” Radio Farda, May 16, 2018. Archived at https://perma.cc/A7ZR-KQ52.

- “Closing of the Gates” Center for Human Rights in Iran. 2018. Archived at https://perma.cc/5Y56-UPLM.

- “Dozens of Specialists and IT Entrepreneurs Letter to Hassan Rouhani” Itmen. Archived at https://perma.cc/W877-RCNG.

- Kargar, Simin. “Iran’s National Information Network: Faster Speeds, but at What Cost?”. Internet Monitor, February 21, 2018. Archived at https://perma.cc/UCK2-GENL.

- “Iran Ranked World’s 7th Instagram Users” Financial Tribune, February 5, 2018. Archived at https://perma.cc/3NRE-C7QU.

- Accurate usage estimates for the various circumvention tools in Iran are not available.

- For example, SOCKS5, PPTP, L2TP, and others. For definitions, see: https://it.uu.se/edu/course/homepage/sakdat/ht06/assignments/pm/programme/odiyo-dwarkanath.pdf. Archived at https://perma.cc/LQ3G-AXF8.

- The TLS Handshake Protocol is a widely used encryption protocol used to establish a secure session to exchange information over the Internet, for example between a web server and a browser, or sending email. https://www.cloudflare.com/learning/security/glossary/transport-layer-security-tls/.

- Milad Nouri (MidlaDnu). [Mr. JAHROMI, unlike messaging applications we do not expect a 5-billion loan, major state subsidies, or other excessive expectations. Our mere request is to let us continue using VPNs in order to bypass the US sanctions that deprive Iranian businesses from using various website and services (e.g Android, Firebase, and Google Analytics) and keep our businesses alive. May 15, 2018. 9:26 A.M. Tweet. Archived at https://perma.cc/D5VC-NA9A.

- “Soroush Messenger” Cafe Bazaar. Accessed August 8, 2018. Archived at https://perma.cc/BC7C-R2F4.

- “Soroush Messenger” Google Play Store. Accessed August 8, 2018. Archived at https://perma.cc/WU8N-5B3J.

- “Soroush Messenger” Google Play Store. Accessed March 31, 2018.

- “Gap Messenger” Google Play Store. Accessed August 9, 2018. Archived at https://perma.cc/8FW8-2Q4H.

- “Wispi” Google Play Store. Accessed August 9, 2018. Archived at https://perma.cc/7DZR-AREQ.

- “جهرمی: تنها هفت میلیون کاربر پیامرسان داخلی نصب کردهاند” [Jahromi: Only seven million users have installed internal messengers]. Radio Farda. Archived at https://perma.cc/UU7U-4PWV.

- Sheikhi, Marjohn. “ICT min. Says domestic messaging apps have 10.5 active users” Mehr News Agency, May 28, 2018. Archived at https://perma.cc/ABF6-2WS3.

- “App Annie” App Annie, Accessed August 8, 2018. Archived at https://perma.cc/FU34-HZFP.

- “Top Free in Communication” Google Play. Accessed August 23, 2018. Archived at https://perma.cc/8GZ5-N3CC.

- TahaYasseri is Assistant Professor of Computational Social Sciences, Oxford University's Internet Research Center, Ph.D. in Physics from the University of Göttingen, Germany, and a master's degree from the Faculty of Physics, Sharif University of Technology. Telegram Message. Archived at https://perma.cc/FMS4-SZ3F.

- Ibid.

- The government’s official statement on May 1, 2018 blamed the Judiciary’s unwarranted interference in Iranians’ access to information and argued that the Supreme Council of National Security had sole authority to determine the extent to which a technology poses a risk to national security. http://dolat.ir/detail/307750. Archived at https://perma.cc/DB76-HXQB.

Research Bulletins

- Internet Censorship and the Intraregional Geopolitical Conflicts in the Middle East and North Africa

- Censorship and Collateral Damage: Analyzing the Telegram Ban in Iran

- The Yemen War Online: Propagation of Censored Content on Twitter

- Iran's National Information Network: Faster Speeds, but at What Cost?

- The Slippery Slope of Internet Censorship in Egypt