Iran's National Information Network: Faster Speeds, but at What Cost?

Iran's National Information Network: Faster Speeds, but at What Cost?

Despite the Iranian government’s extensive marketing campaign to promote its National Information Network as a faster and cheaper service, users’ preference towards internationally hosted content and tools remains undeniable and challenging to change.

by Simin Kargar

It was a challenging start to the new year for Internet users in Iran. Between late December and the second week of January, anti-government demonstrations broke out as a reaction to economic grievances. The demonstrations escalated to political unrest in multiple towns around Iran and led to many arrests and a high death toll.[0]

Telegram and Instagram were key organizing tools to share information about demonstrations and videos of gatherings. Several Telegram channels were involved in inciting violence and terror, which led to Telegram blocking one of them.[0] The Iran government reacted to the central role these platforms played in fueling the protests by temporarily blocking Telegram and Instagram.[0] As OONI documented,[0] the ban went into effect on December 31 and was lifted on January 13.[0]

Disruptions were not limited to the blocking of international platforms. On January 1, one of Iran’s upstream connections to the global Internet went down for several hours. The disconnection, which appeared to have been caused by a technical issue, led to a substantial decrease in international bandwidth.[0] For Iranians, the disruption fed into concerns that the government had sought to curtail global connectivity amid the protests.[0]

The National Information Network improves the government’s capacity to throttle international Internet traffic at will—a significant instrument during politically critical times.

There are still legitimate reasons to fret about potential interference with Iran’s connectivity to the global Internet. The desire to control the global Internet has been core to a larger development known as the National Information Network (NIN), a concept that was first introduced in 2006 but accelerated in technical development under the first term of President Rouhani.[0]

Thus far, Iran appears to have finalized the technical groundwork for separating international Internet traffic from domestic.[0] This allows Iran to keep traffic sent between Iranian networks inside the country, and it provides the infrastructure for hosting content inside Iran. In particular, the NIN was promised to protect national security by offering sovereignty in cyberspace through reducing the state’s dependence on international services. As such, the NIN improves the government’s capacity to throttle international Internet traffic at will—a significant instrument during politically critical times such as protests. Notwithstanding the NIN development, the practice of throttling has a much longer history in Iran, as researchers have previously documented.[0]

The NIN is designed to bring about a more cohesive content consumption pattern by Internet users in Iran—one that stirs traffic toward state-approved content hosted on the NIN. Iran has pursued this strategy by offering faster speeds and lower costs to users.[0] This has been facilitated by the creation and deployment of data exchange and content delivery centers around the country, which has led to a significant reduction in data transfer costs and an increase in bandwidth.[0] Consequently, users enjoy increased Internet speed with a 50% discount for data consumption when accessing domestically hosted sites or services, rather than those hosted internationally.[0]

Has Iran’s push to encourage domestic content consumption and hosting been effective?

Telegram has been the most popular messaging application in Iran in recent years, with an estimated user base of 40 million in a country with 47 million mobile Internet users.

The significant increase in the usage stats of popular circumvention tools indicates a staggering difference between the users’ choice and the state’s desired pattern. Proxy tools such as Psiphon[0] and Lantern[0] are frequently used by Iranians to bypass state censorship and access information that is typically blocked. As noted earlier, consumers using circumvention tools to either bypass state restrictions or to browse locally hosted websites anonymously will not receive the 50% discount.[0]

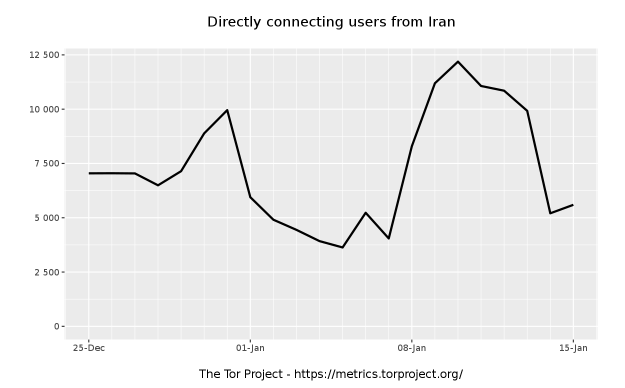

The disruption of international Internet traffic and blocking of Telegram during the protests drove significant numbers of Iranians to these tools. For example, the number of unique users of Psiphon in Iran soared from about 3 million to more than 10 million per day on January 1 and 2.[0] Tor usage peaked around the same time.[0]

These peaks during the recent protests suggest an important pattern in users’ behavior: despite the extensive marketing campaign for promoting the NIN as a faster and cheaper service, users’ preference towards internationally hosted content and tools remains undeniable and challenging to change. The causes appear to have roots in the following:

Popularity

Telegram has been the most popular messaging application in Iran in recent years,[0] with an estimated user base of 40 million[0] in a country with 47 million mobile Internet users.[0] Such popularity has led a community of 10,000-15,000 entrepreneurs to establish their small businesses solely on Telegram. They regularly use the platform to conduct marketing, process orders, and offer customer support.[0] Some businesses estimate losses of over 95% of their income as a result of blocking of Telegram.[0]

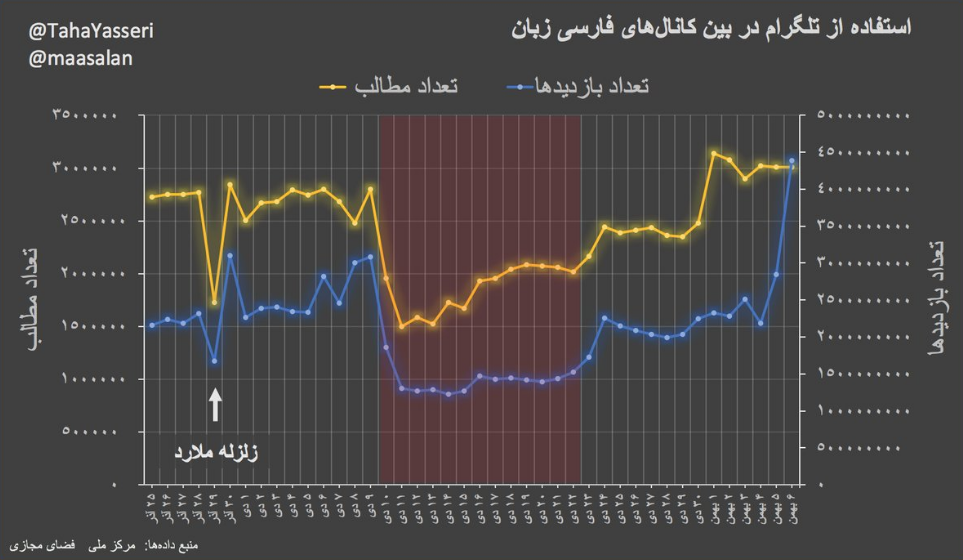

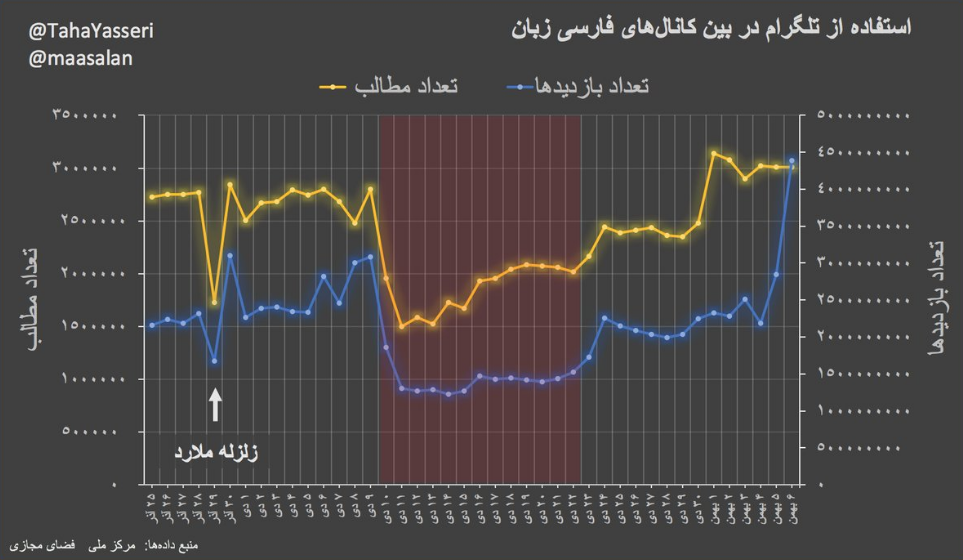

While the temporary ban on the platform affected the reach and activity of public Telegram channels,[0] researchers at Oxford Internet Institute recently documented that these indicators are on the rise again after a brief decline.[0]

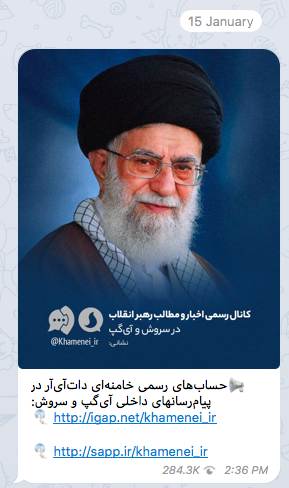

The blocking of Telegram forced some users to migrate to alternative tools. Homegrown applications such as Soroush and iGap observed an increase in downloads. By October 2017, these applications had been downloaded 200,000 and 50,000 times, respectively.[0] By January 3, downloads of Soroush had jumped to 500,000.[0] Another sharp rise came about after the Supreme Leader publicly endorsed these applications by publicizing his accounts on Soroush and iGap. Ironically, the promotional message was disseminated via the Leader’s Telegram channel, which has over 1 million members.[0] In less than two weeks following the announcement, Soroush installations doubled to over a million on Cafe Bazaar, the Iranian play store.[0] Most of these new installations are suspected to come from conservative users and ideological followers of the Supreme Leader. It remains to be seen if the growth rate of these applications will continue now that Telegram and Instagram are accessible again.

Quality and Reliability of Information

Another major component of the NIN is national search engines such as Parsijoo and Yooz that render search results of state-approved—and sometimes fabricated—content. This is implemented through systematic keyword filtering and directing users to state-approved websites. For example, top search results on Parsijoo[0] for “Masih Alinejad”, a controversial journalist who runs an online campaign against compulsory hijab in Iran, return state propaganda against Masih and her work.[0] The same search on Google returns her Facebook page and interviews with credible media sources such as the BBC.[0]

With over $6 billion invested, the NIN is the most costly national telecommunications project in the history of the Islamic Republic.

In 2016, state officials reported 600,000 daily visits and 120,000 search queries on Parsijoo.[0] According to the authorities, Parsijoo had become the second most popular search engine in the country after Google. However, Alexa rankings still indicate that Google is the most visited website in Iran. None of the domestic search engines show up among the top 50 websites.[0]

Trust and Safety

Critics of the NIN have continued to warn about its implications for access to information as well as security and privacy of users’ data.[0] Following the unblocking of Telegram, a member of Iran’s highest policy making body for cyberspace defended homegrown applications as they would facilitate the state’s control over these platforms.[0] The statement, which was made in a televised interview, was interpreted by users to signal the state’s intention to access users’ data through these applications. Users have repeatedly —and often humorously[0]—raised concerns about security of these platforms. Some, for example, documented the lack of encryption on Soroush as an indication of it being insecure and therefore non-trustworthy.[0] The climate of skepticism is even prevalent among the less tech-savvy generation who have voiced their concern over these state-endorsed tools.[0]

A Grand Investment with Grave Challenges Ahead

With over $6 billion invested, the NIN is the most costly national telecommunications project in the history of the Islamic Republic.[0] Other affiliated costs align well with the NIN’s overarching goals: $1.5 billion on a domestic search engines project[0] and $135,000 in additional subsidies to go toward mature development of domestic messaging applications.[0] This strategy is to substantially cut reliance on international application such as Telegram.

The recent events in Iran put the investment to the test and underscored the challenges of fundamentally changing user behavior. While an increase in speed allows for services that potentially improve access and more sophisticated information sharing, these benefits only apply to domestically hosted platforms that have not been popular. As the recent protests affirmed, when popular international tools became inaccessible, users showed little interest to limit their traffic to domestic websites and tools, even at a discounted price. Despite Iran’s concerted efforts to popularize the NIN’s application, appealing to users and acquiring their trust may be much harder than the government had envisioned.

References

- Kara Dapena and Asa Fitch, 247 Demonstrations, 90 Cities, 14 Days: Iran’s Upheaval, Wall Street Journal, 19 January 2018.

- Jon Fingas, Telegram suspends channel for encouraging violent Iran protests, Engadget, 30 December 2017.

- Iran protests: Telegram and Instagram restricted, BBC News, 31 December 2017.

- Maria Xynou, Arturo Filastò, Iran Protests: OONI data confirms censorship events (Part 1), OONI, 5 January 2018.

- Iran unblocks Telegram messenger service shut down during country-wide protests, Deutsche Welle, 14 January 2018.

- InternetIntelligence on Twitter, 1 January 2018.

- Kavé Salamatian on Twitter, 1 January 2018.

- Matt Vasilogambros, Iran's Own Internet, The Atlantic, 29 August 2016.

- Guards at the Gate; The Expanding State Control Over the Internet in Iran, Center for Human Rights in Iran, January 2018.

- Collin Anderson, Dimming the Internet: Detecting Throttling as a Mechanism of Censorship in Iran, 18 June 2013.

- Tightening the Net; Internet Security and Censorship in Iran, ARTICLE 19, 2016.

- Op.cit 9, p 41.

- 50% discount on visiting select websites, Irancell.

- Psiphon

- Lantern

- Elmira Babaiee, Irancell responds to the ambiguity of Internet packet usage with VPN, Shargh Daily, 9 May 2017.

- Sam Schechner, How Millions of Iranians Are Evading the Internet Censors, Wall Street Journal, 9 January 2018.

- Tor Metrics

- MohammadReza Azali, Infographic: Telegram Usage Statistics in Iran, Techrasa, 6 September 2017.

- Murtaza Husein, Amid Protests, Iran’s Government Censors Its Critics With Chinese-Style Internet Control, The Intercept, 13 January 2018.

- Masoumeh Bakhshipour, The Latest Status of ICT Penetration Rate : 47 Million Iranians Use Mobile Internet, Mehr News Agency, 11 November 2017.

- Holly Dagres, Inside the world of social media advertising in Iran, Al-Monitor, 16 November 2017.

- Maysam Bizaer, Internet censorship a double-edged sword for Tehran, Al-Monitor, 12 January 2018.

- Taha Yasseri on Twitter, 10 January 2018.

- Taha Yasseri on Twitter, 27 January 2018.

- Hossein Sharafi on Twitter, 23 October 2017.

- Amir Mostakin, Growth in the installation rate of Iranian messenger apps this week, Digiato, 3 January 2018.

- Ayatollah Khamenei’s Telegram Channel.

- Soroush Messenger on Cafe Bazar.

- Search results for “Masih Alinejad” on Parsijoo search engine.

- My Stealthy Freedom page on Facebook.

- Search results for “Masih Alinejad” on Google.

- ‘Parsijoo’ most used search engine in Iran after Google, Mehr News Agency, 31 October 2016.

- Top Sites in Iran, Alexa.

- Op.cit 9, p 23.

- Mehdi MMJ on Twitter, 16 January 2018.

- Ghaem Hosseini on Twitter, 14 January 2018. “I was chatting with a young woman over Soroush, trying to seduce her with my luxurious car and high salary. I immediately received a text message from a government bureau that I was no longer eligible for state subsidies!” The user suggests that real-time surveillance of all communications takes place over domestic applications.

- Mohamad Hosein on Twitter, 22 January 2018.

- Golnaz Esfandiari, After Protests, Iran Leadership Pushes Hard For 'Homegrown' Apps, Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, 20 January 2018.

- 10 Things You Should Know About Iran’s Multi-Billion Dollar National Internet Project, Center for Human Rights in Iran, 13 October 2016.

- Masoumeh Bakhshipour, $1.5 Billion Support for Two Native Search Engines, Mehr News Agency, 21 January 2018.

- Supreme Council of Cyberspace to provide $135,000 in loan to developers of native messenger applications, ITNA, 16 January 2018.

Research Bulletins

- Internet Censorship and the Intraregional Geopolitical Conflicts in the Middle East and North Africa

- Censorship and Collateral Damage: Analyzing the Telegram Ban in Iran

- The Yemen War Online: Propagation of Censored Content on Twitter

- Iran's National Information Network: Faster Speeds, but at What Cost?

- The Slippery Slope of Internet Censorship in Egypt