Internet Blackouts Have Unintended Consequences

When governments order nation-wide internet blocks for political reasons, more than just the political atmosphere is at stake. The increasingly cyber-integrated culture many of us live in flounders when the internet is no longer accessible. During the 2011 Egyptian revolution that overthrew Mubarak, the internet was blocked throughout the country for a week (January 27 to February 2, 2011), during which the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development estimates that Egypt incurred a loss of at least 90 million USD as a result of the block. Egypt’s government-mandated blackout is one of the longest to date, but large scale internet blackouts of entire countries did not end when the Arab Spring lost momentum.

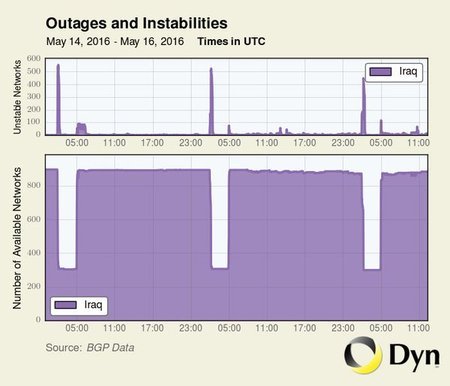

For a three day period of May 14-16 of this year, the Iraqi government shut down the internet between 5am and 8am each day, coinciding with exams for secondary and high-school students in the country. While secondary and high school students may have received error messages on their phones when they tried to search for answers online during the national exam, Iraqi citizens’ free-speech rights were impinged upon by not being able to access the external world through the internet. A blackout can delay emergency services, help governments escape scrutiny in cases of abuse, and have the potential to seriously harm the economy of a country.

The image above from Dyn Research shows the number of available networks in Iraq for the three day period. It’s easy to see the dip in the amount of networks available at the same time for the three days. (The reason that the number of available networks doesn't drop to zero is because the Kurdish controlled area of Iraq has its own internet governance, as we highlighted in this blog post last month.) While no one is suggesting that the Iraqi government shouldn’t take cheating on national exams seriously, many wonder if shutting down the internet to mitigate cheating is worth the multitude of implications of an blacked out internet. Doug Madory, Dyn’s director of internet research, states that “it isn’t hyperbolic to say that the government of Iraq faces multiple immediate existential threats—placement exams aren’t on that list, I would think.”

Suspending the internet in order to prevent cheating is not unique to Iraq. In February 2016, the Indian province of Gujarat shut down the availability of mobile internet services while the Accountant’s Recruitment Exam (Talatis) was taking place. The internet shut down took place following the leak of the Talatis exam just the year prior. In December 2015, Twitter, Facebook, and other social media sites were blocked in Algeria during baccalaureate exams. In Ethiopia, Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and Viber were blocked during university exams this July. In August 2014, Uzbekistan telecom companies shut down the internet for "urgent maintenance work on telecommunications networks,” though many believe that the shutdown was done to prevent cheating on national university exams because the network disconnection coincided exactly with the timing of those exams.

As curious as the case of internet blockage in order to prevent cheating on national exams may be, internet blackouts occur more commonly because of a government’s desire to suppress political upheaval. During the February 18, 2016 election in Uganda, which resulted in the reelection of Yoweri Museveni for a fifth term, the Uganda Communications Commission ordered mobile network operators to shut down key social media sites like WhatsApp, Facebook, and Twitter and disable mobile money platforms. The same also happened on the day of Museveni’s swearing into office in May of this year, most likely to prevent the mobilization of protesters. Around the time of the election, the blockage of money mobile platforms lasted for almost four days. 35% of Ugandans have money mobile accounts, which are used to pay school fees, utility bills, and even salaries, meaning that a lack of access to mobile money accounts has a serious impact on the Ugandan economy. But it turns out that in shutting down these important platforms, the Ugandan government might have also hurt itself: the Uganda Revenue Authority taxes revenues earned from mobile money transactions both by agents and mobile money providers at 10%, and mobile operators are some of the largest taxpayers in the country. In an opinion piece in Circle ID, Douglas Onyango, a Ugandan who experienced the internet blackout, wrote, “I can tell you this much: using internet blackouts to suppress free speech is like chasing a wild-goose: governments do not get the intended results. Instead, the collateral damage foments resentment, mistrust, and wrecks irreparable reputation damage.”

One of the most prominent groups advocating for an end to internet blackouts is Access Now, which has recorded 20 government-mandated internet blackouts in 2016, already more than the total number of blackouts in all of 2015. Advocacy groups have moved the UN to recognize that internet blackouts affect everyone’s rights. the UN addressed the issue in a non-binding resolution at the June 2016 assembly in Geneva. The resolution affirmed “that the same rights that people have offline must also be protected online, in particular freedom of expression, which is applicable regardless of frontiers and through any media of one’s choice." Specifically on the topic of internet blackouts, the resolution called for “expanding access to Internet and request[ed] all States to make efforts to bridge the many forms of digital divides." Russia and China proposed amendments that would dilute the strength of the resolution, but were met with opposition from civil society organizations and other member countries.