Translating Tweets, Traversing Cyberspace: A Digital Trip with the "Out of Eden" Walk

Online Language Communities: The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly

On good days, I typically log into my Facebook account, check out the latest cyberslang my former Turkish university students have crafted, and rejoice in the Internet's diverse linguistic ecosystem. I peruse the latest legal news in the Arabic blogosphere and most recently published political cartoons in Le Monde. Occasionally, I get ambitious and try to read a few pages on Pashto Wikipedia. I do not speak these languages fluently, but I've studied them and come to love them for their idiosyncrasies and for the gems that their speakers have to offer.

On bad days, I see the Internet as a linguistic prison, a place of infinite language barriers that seem almost as intimidating and impermeable as the great Chinese firewall. I come to terms with the ways in which my English privilege confines others; I surf Twitter, Google away, and think of all the other language communities that remain isolated and entangled by their monolingualism.

I believe that the offline world has made substantial progress in providing better support to minority language groups. The U.S. Department of Justice is working to dissolve language barriers in the courtroom; the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia, the International Criminal Court, and the Special Tribunal for Lebanon have followed in the footsteps of Nuremberg's International Military Tribunal by developing their own Translation & Interpretation Units. The New York City Department of Education has hired a number of translators to help immigrant parents understand the never-ending flow of school documents that their children bring home. Translators, from the literary to the legal, are beginning to deliberate how to best empower themselves as well as their clients.

But, cyberspace is largely another story. In 2009, Ethan Zuckerman summarized the problem of the polyglot Internet: "We are all experiencing a smaller Internet than we should be. In the user-created Web, we've created a weird dynamic where there is more out there every day - some of it important - but each person can individually read less of it because it's in multiple languages."

A number of researchers have substantiated his concerns in the past few years. In October 2011, a Semiocast study of 5.6 billion tweets revealed that more than 2 million public messages were posted every day on Twitter in Arabic, up from about 30,000 in July 2010. Two years later, in 2013, Internet World Stats estimated that the number of English speakers only represented 28.6% of all Internet users. This map by two researchers at the Oxford Internet Institute helps visualize how digital divides and language barriers collide.

There have been a number of recent endeavors to make room for more language groups online and to provide them with the tools they need to express themselves. In October 2013, ICANN, the organization that sets domain name standards like “.com” and “.org,” created four new suffixes: شبكة, онлайн, сайт, 游戏. [Dan Kedmey of TIME noted, "That’s Arabic for “web,” Cyrillic for “online” and “site,” and Chinese for “game.”] Twitter opened a Translation Centre in October 2009 and convinced over 400,000 volunteer translators (from nearly 50 language groups) to help localize twitter.com, mobile.twitter.com, Twitter for iPhone and iPad, Twitter for Android, Twitter Help and the Twitter Business Center. Global Voices (GV) launched its Lingua Project in 2006 and has since recruited a community of 500 volunteer translators to help render underreported stories into more than 35 languages; part of their work involves translating tweets and embedding them into the articles published on the GV website.

This principle came into play in 2012, when George Weyman, then director of Meedan, a social technology nonprofit, published a blog post titled "Translating Tweets from the Arab Spring: Towards a Translation Workbench for Twitter." Highlighting the growth of the Arabic web, he asked these questions, among others:

- How would you translate hashtags?

- Would you expect URLs in translation?

- Who would you like to translate your tweets?

Weyman's questions helped promote the idea that translating tweets required ethical, methodological, and technological forethought.

Dissolving Language Barriers One Tweet at a Time: The Out of Eden Walk

Several years later, Paul Salopek, a two-time Pulitzer Prize-winning writer, proposed to trace the path of human migration by taking a seven yearlong walk. His aim was to start in January 2013 and end in 2020, beginning his trek in Ethiopia and concluding his journey in Tierra del Fuego, Argentina. In his project proposal, he reflected, "TO CALIPER the continents with my legs in seven years, I will walk on average 15 miles a day—about five hours—for half of each year. The remaining time will be spent on logistics, recuperation and writing."

Salopek's worldwide trek consists of multiple journalistic components; he received support from a host of individuals and institutions [http://bit.ly/1Sx8ved] to write, research, and of course, walk. One collaborative product of his initial efforts was called Spotlight: as he journeyed northward across the Middle East, from the desert near Maqna, Saudi Arabia to a Syrian refugee camp in Jordan, volunteers from Meedan, the Dolly Project, and Translators Without Borders selected geo-tagged Tweets by people within a one-mile radius of his path and translated them into English. These Spotlights were then posted on the Out of Eden Walk website for all to see, making it possible for people to read the translated tweets without visiting Twitter directly.

A little background: today, it is possible to tweet in many different languages, including Basque, Farsi, and Arabic. Yet, despite these successes, language barriers still permeate cyberspace, however multilingual it might be, and Twitter is no exception. Tweets, the 140-character messages that make the platform popular, remain largely untranslated, even though users communicate in over 61 different languages. For years, translators have been perplexed by the unexpected complexity of a short and snappy Tweet. Berkman affiliate, Zeynep Tufekci notes that tweets have an oral texture, that they resemble conversations in their style and structure. Sadie Stein of The Paris Review delves further and laments, "Is Twitter a genre? I'm afraid it might be." There's little consensus over what a tweet represents or is, and for translators, this ambiguity can prove especially challenging.

In the past few years, people have started to translate tweets by political figures and celebrities. (Full disclaimer: I briefly maintained @FRPolTweets, where I translated select tweets from Nicholas Sarkozy, François Hollande and Marine Le Pen into English; I've also interviewed at least one activist translator of pro-Catalan independence tweets, and this summer, as an intern at the Berkman Center, I've translated French and Arabic tweets for research purposes.) But, I'm not the only one to experiment in the rocky and unruly terrain of Twitter translation. Some have tried translating tweets by ISIS, Miley Cyrus, Justin Timberlake, and a slew of others. There are now even apps to translate your favorite K-pop idols' tweets into English.

The Out of Eden Walk's translation efforts helps translate the thoughts, comments, and micro-length reflections of ordinary netizens, not those with thousands or millions of followers. Its volunteer translators lift tweets from near Gaziantep, Turkey; Pyla, Cyprus; Ghor al Safi, Jordan; Maqna, Saudi Arabia, take them off Twitter; translate them into English; add paratextual information; and plop them onto their own website.

Confused? This is how members of the translation project describe their process: "We collaborate with Map-D’s Tweetmap, a powerful data analysis tool for geolocated social media data, to pull Tweets in the region. We then sift through the posts — a rich variety of inside jokes, @replies and any variety of messages — for the gems that speak to us and tell a story. We begin first with a thorough curation session, sifting carefully for messages that might offer an additional cultural insight or perspective. Then, not only do we translate the content of the message, we also provide annotations that help tell the background story and assumptions that might be present. A Tweet about Hadag Nahash music in Israel, for instance, merits a brief description of the genre, which might be unfamiliar to English-speaking readers."

An Xiao Mina, Director of Products at Meedan, also posted this additional information to explain how volunteers select tweets to translate along Salopek's route: "When we curate, we often ask ourselves, what does this tweet say about the region? How can it be used as a vehicle for storytelling? Is it interesting by itself, or is it interesting when supported by other documents, like a link to a news story or an entry in Wikipedia?" She emphasized that Meedan aims to select and translate tweets that do the following:

- Show an image of the region

- Provide insight into a cultural nuance

- Share a bit of humor or whimsy

- Show the mundane

- Shed light on current events of local, national or international importance"

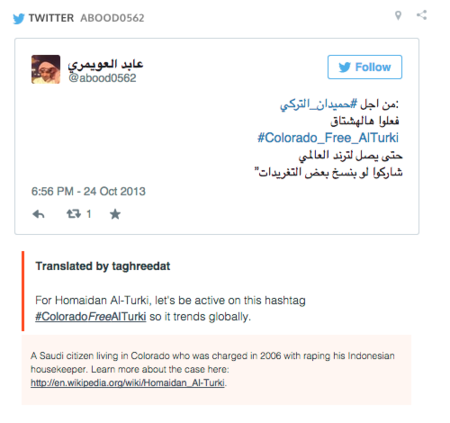

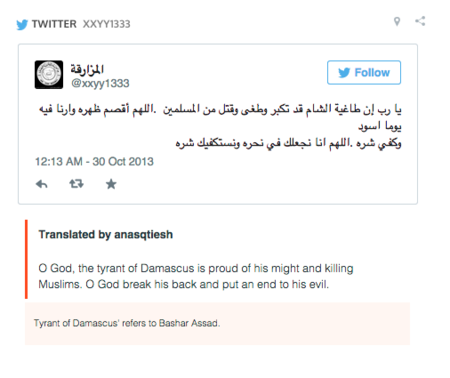

Ranging from polysyllabically pensive to hyperbolically hashtagged, the translated tweets reveal the concerns, interests, and thoughts of individuals around the world. In one Spotlight, on the pilgrim trail from Cairo to Mecca, @abood0562 calls for increased hashtagging on behalf of an alleged Saudi rapist, and within the same mile-radius, @xxy1333 pleads for the cessation of violence in Syria.

In another Spotlight, Sevgim Deniz Egilmez translated the two below tweets from near Gaziantep, Turkey:

Today, there is no consensus on how to translate tweets and present them online, but the Out of Eden Walk's Spotlightsrepresent one approach that is trying to make sense of the murky, muddled, and multilingual digital world. It's far from a flawless platform. Not all tweets have paratextual commentary (and in some situations, expressive phrases like @BaklavaPover's "Oooo," do not make it into the English translations). Furthermore, not all tweets are properly translated; in the case of Sevgim Deniz Egilmez's first translation, she employs an incorrect tense (sent vs. send), but readers can still deduce the general emotion and intent of the tweet.

It's unclear what future translation as a whole has on Twitter. While, at this juncture, there haven't been any Spotlights posted since September 10, 2014, others, such as Global Voices, continue to forge ahead, translating tweets and embedding them in news stories.

There are multiple directions that Twitter translation efforts could take in the next decade, but right now, the field still suffers from a few problems:

(1) There is almost no money in translating tweets.

(2) Some translators are often uncertain of how to address questions of copyright, authorship, ownership, and attribution in Twitter's digital ecosystem.

(3) There are very few seminars available on Twitter translation, and most, like this half-day course run by the Public Works and Government Services of Canada, put rigid emphasis on "respecting the original message" instead of encouraging innovative approaches.

(4) Unlike the more traditional literary publishing industry, Twitter's infrastructure does not have many mechanisms in place to protect against faulty, abusive translation practices.