The Sinar Project shines light on Malaysian Internet Censorship

The Sinar Project shines light on Malaysian Internet Censorship

This post is part of an Internet Monitor blog series interviewing Internet researchers about their work and experience with Internet censorship. In this installment, IM Research Assistant Dan Bateyko talks to Khairil Yusof , co-founder and coordinator of the Sinar Project , a Malaysian non-profit initiative working with open source and civic technology to better transparency, accountability and digital rights. Khairil walks us through Sinar Project’s work documenting and responding to Malaysian Internet censorship. Quotations have been edited and condensed for clarity.

Last week, Malaysia wielded its new Anti-Fake News Bill for the first time. While traveling in Kuala Lumpur, a Danish citizen pleaded guilty to “maliciously publishing false information” after posting a YouTube video critical of the Malaysian police’s response to a murder. When I read the news, I went looking for the YouTube video in question to judge for myself how bad his comments were. But none of the news outlets included a link to the video — likely because if they share it, they risk being convicted under the law too.

When the Malaysian legislature put the region’s first “fake news” regulation into law last month, they granted government the power to punish citizens who maliciously create or share fake news. But sharing could mean anything from posting on Facebook to something as small as a retweet. In this case, the Danish YouTuber will only serve a month, though under the law, fake news offenders can be charged up to 129,000 USD and sentenced to six years imprisonment. As Global Voices highlights, the fake news bill similarly affects app makers, website administrators, and forum moderators. While the government claims the bill will help combat misinformation by making the public act more responsibly, human rights activists worry that it will be used to muzzle speech during the 14th General Election. These worries in no small part stem from the country’s bouts of politically-motivated Internet censorship.

In 2011, Prime Minister Najib Razak vowed to continue his predecessor’s commitment to never censor the Internet — a promise grounded in part by the hope that a censorship-free Internet would attract tech companies to Malaysia. But in 2015, the independent news website Sarawak Report published an article implicating the Prime Minister in a corruption scandal in which millions of dollars were diverted from the sovereign wealth fund, 1Malaysia Development Berhad (1MDB), to his personal accounts. As further reports on the scandal came in, the media regulator cut off access to a number of newspapers reporting on the story and even blocked the blogging platform Medium, which hosted news stories by Sarawak Report. The Malaysian Communications and Multimedia Commission (MCMC) reasoned that these websites were sharing content that might threaten the nation’s stability. Now human rights defenders are particularly concerned the Anti-Fake News Bill will restrict access to information about the scandal; a Malaysian deputy communications minister already described the Wall Street Journal, the New York Times, and MSNBC coverage of the 1MDB scandal as fake news.

The Sinar Project knows well that tracking government spending is challenging, even without the threat of censorship. Taking its name from the Malay word for “light,” the Sinar Project began as an initiative to make public finance open and keep politicians accountable. As part of that work, the Sinar Project is building a website for Malaysian voters to access basic information about candidates, as well as a list of “blacklisted candidates” who Sinar Project categorize as being involved in corruption or otherwise undemocratic conduct. Because an open Internet is critical to their mission, the Sinar Project also provides regional technical support and documents Internet censorship, collaborating with the Open Observatory for Network Interference (OONI) to run daily censorship tests on 1152 global and local websites.

I spoke with Khairil Yusof, co-founder of the Sinar Project, in December 2017 about how the Sinar Project started measuring Malaysian Internet censorship, the state of Internet rights throughout Southeast Asia, and the team’s goals for 2018.

Early days

Sinar Project’s work on Internet censorship began in 2013, when in the run-up to the 13th General Election, reports came in that opposition-related political websites were inaccessible.

“Two or three groups including us independently verified that there was some sort of deep packet inspection happening at one of the ISPs and that was the first time that we started getting involved in digital rights and internet censorship — when we realized our work for open government, which is highly Internet based, could be affected.” Yusof said. “This is pre-Snowden, so HTTPS wasn’t prevalent,”Yusof said referring to a protocol that helps prevent Internet providers from blocking specific web pages on a site. (To learn more, see Internet Monitor’s explainer.)

Then in 2014, Malaysian users noticed they no longer had access to a BBC article describing memes satirizing the Prime Minister. The Sinar Project again conducted measurement tests to determine the source: “We only found deep packet inspection on one ISP, T.M. Net (Telekom Malaysia) and it was not official and it didn’t happen on other ISPs. So the suspicion here was that it might be a rogue operator or some testing of some censorship tools.”

Internet censorship is often a cat-and-mouse game; as Internet users look for ways to route around the censorship, media regulators adapt their practices. After these incidents, Malaysian political websites began moving over to HTTPS to resist against targeted blocking of articles.

“But in 2015, especially after the 2013 elections, almost every kind of political site including social media all moved over to HTTPS so deep packet inspection did not work anymore. So the official way the government censors the Internet in Malaysia is basically through a notice to the ISPs, where they say that you have to block this site and to apply a block or censor. They would actually apply a DNS redirection , which then redirects to the official notice,” Yusof said.

“Until 2015, the official status has always been that ‘we do not interfere or censor the Internet’, but with the [2015 censoring of] Sarawak report and Malaysian Insider, it was the first time that the government actually made an official statement saying that ‘we are going to censor these sites’ along with a redirect blocked notice with the official statement,” Yusof said. “So our approach was then ‘Okay. Now that we know that it’s official, how are they censoring it?”

To answer that question, Sinar Project started their Digital Rights Monitor project, which records incidents of Internet censorship. As an open data proponent, Yusof is not content with anecdotal evidence. “If you look at [Internet censorship stories], they all cite newspaper reports and these newspaper reports are often not data-backed, just expert or journalist [testimony],” Yusof said, cautioning that what looks like censorship to a reporter could just be a local network problem. In response to these concerns, the Sinar Project worked with (OONI) to release a report on Malaysian censorship, which confirmed that ISPs continue to filter websites that cover the 1MDB scandal.

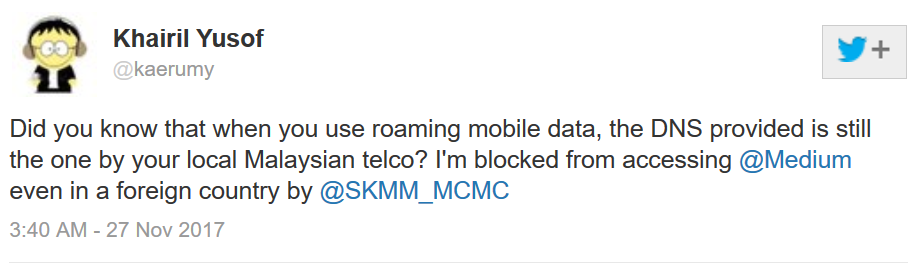

According to Yusof, that website censorship follows Malaysian citizens even as they travel to other countries.

“You’re still using the DNS of your ISP provider in Malaysia, no matter what country. So you see it here — if you’re roaming even if I’m on a different network overseas, If I’m roaming with my Malaysia Teleco for data I still still get sites like Medium blocked.”

While the Malaysian Communications and Multimedia Act of 1998 contains a clause that purportedly guards against Internet censorship, a section concerning the improper use of network services to make “obscene, indecent, false, menacing or offensive” comments has frequently been used against individuals posting online. Yusof also points to Section 263 points out at least one clause that enable Internet censorship.

“Section 263 is a section governing the licensees for the Internet providers. Internet providers in Malaysia are licensed to provide Internet service, so Section 263 basically says that the ‘licensee should use his best endeavors to prevent network facilities from committing any offence under the law of Malaysia.’ ‘ That shall endeavor to prevent ’ is a preemptive condition for possible violations. So this is the current way that they’re implementing censorship in terms of the regulatory framework; they’re using their provisions for licensees, which are the ISPs, to give them the notice that says ‘you have to implement some sort of censorship, in this case DNS hijacking, for a possible violation,” said Yusof. “In this sense it’s pretty bad, because the MCMC does not have to actually prove that the violation actually occurred — just a possible violation of it.”

As Freedom House’s “Freedom on the Net” 2018 report highlights, MCMC’s blocking requests lack transparency or ways to appeal the block. “They are not justifying it with any legal or formal documents, they’re just ordering ISPs to block,” Yusof said. “We feel this is too much power. It can affect a lot of freedom of expression but the MCMC can do this without any legal or check and balance.”

Regional Challenges to Documenting Internet Censorship

In the Diplomat’s “The Rapid Rise of Censorship in Southeast Asia,” Freedom House’s Asia research analyst Madeline Earp argues that “censorship is on the rise and internet freedom is declining in Southeast Asia” and notes that seven out of eight Southeast Asian nations Internet freedom scores dropped this year. As part of an effort to document the rise of regional Internet censorship, the Sinar Project helped convene a workshop to teach civil society partners how to run OONI network interference tests.

“We started doing testing in Malaysia but we heard that rights organizations in our region were also monitoring internet censorship. We got a small grant from Access Now to support and expand similar efforts in testing censorship data.” said Yusof.

At the workshop, participants contributed to lists of websites to monitor for censorship. These lists often have overlap; when a news website in one country can be blocked in a neighboring one, it’s vital to have an awareness of regional media. Yusof highlights technical proficiency as one barrier to adoption, as many human rights NGOs lack in-house technical support. This poses a problem when members need to contribute through Github or when only one person on staff becomes responsible for the measurement tests. As such, the workshop also helped participants learn the technical skills to run an OONI censorship measurement probe.

Yusof also shared some of the particular challenges of documenting Internet censorship in South East Asia. Creating a list of websites to monitor for censorship proved tricky in places where local laws make some URLs too sensitive for an organization to view and test. In some areas of Southeast Asia, it is common practice for employees to turn off the electricity when leaving the office to save on costs. Yusof can recount at least one amusing incident in which an employee turned off the electricity for the night, shutting down the computers running measurement tests.

Controlling the flow of news, Fall 2017–2018

Malaysian Internet censors also pull content that offends religious sentiments. In fall of last year, Malaysian censors blocked Steam, a popular video-game distribution platform, over the release of “Fight of Gods”, a fighting game that pits religious figures against each other. MCMC called the game “threat to the sanctity of religion and interracial harmony in the country” leading Steam to pull the game from their Malaysian store. Later, in October 2017, MCMC blocked FanFiction.net for failing to remove erotic content.

After a series of large data leaks led to MCMC intervention, the Sinar Project joined civil society in drawing attention to the ways Malaysian government might be manipulating the flow of news.

Last September, Lowyat.net, a popular Malaysian Internet forum and technology website, broke news of a data breach involving millions of Malaysians’ personal data such as addresses and mobile phone numbers culled from telecoms and other sources. Two hours after reporting the breach, Lowyat.net took down the article at the request of the Malaysia’s Internet regulator. While MCMC allowed Lowyat.net to restore the article, the brief takedown led civil society to wonder if MCMC sought to stop news about the breach from spreading. The Sinar Project called for MCMC to provide a full disclosure of how the Lowyat.net article violated the Communication and Multimedia Act and to publish a copy of the takedown notice. A minister later claimed that the takedown was the result of a misunderstanding.

After the leak, citizens scrambled to see if they were affected. Keith Rozario, a tech blogger, set up a website called Sayakenahack.com for Malaysians to check if their personal data had been compromised. But MCMC blocked that website too, on the grounds that Sayakenhack had violated a data protection law.

On January 27, 2018, Malaysia was hit by another data leak — this time involving some 220,000 registered organ donors whose Malaysian Identity Cards information, home addresses, and telephone numbers were made available. Sinar Project joined an open letter signed by civil society organizations calling out the Malaysian government’s mishandling of the data leaks. The open letter states that in both cases “organisations such as lowyat.net or members of the public who exposed the issue have been censured, reprimanded and investigated.”

Looking Forward: Goals for the Future

If we don’t work to protect the space, this is going to have a huge impact on democracy and freedom of expression in the region. It’s going to be a battleground for democracy.

This year, the Sinar Project plans to build an OONI-powered human rights Internet censorship dashboard that will show the censorship status of mainstream websites and independent news. The Sinar Project is also engaging its followers with a new OONI app, OONI Run, for quick response to censorship news: “OONI Run allows us at the Sinar Project to craft specific URLs for users to test …even if it’s not on the test list, we can now tweet a link with the OONI app.”

While documenting Internet censorship and offering advice to circumvent blocks is important, Yusof warns that circumvention technology is an imperfect solution to the chilling effect caused by Malaysia’s strict laws.

“We focus too much on Internet censorship, when it’s not about the technical tools,” said Yusof. “[In Malaysia], you have access to the Internet, you have access to Facebook, but you can’t post anything. We’re doing all these digital security trainings for journalists, but that’s not the issue. They’re relatively safe, they have things encrypted. [But] if If you set up SecureDrop, no one can make use of the leaks; what’s the point if you can’t publish?”

With all this data-backed evidence of censorship, Yusof hopes to one day move the Sinar Project into strategic litigation to determine if Internet blocking is constitutional. “If we still have some semblance of rule of law, we need to to do legal challenges like the EFF or ACLU,” Yusof said. “Because for the digital space, there’s a huge impact from all this censorship and we’re finding we don’t have the legal resources to do it.”

As more people go online in Southeast Asia, Yusof sees a broader battle ahead.

“In this region, digital rights are going to have a massive impact in terms of political expression and freedom and participation. We’re seeing a lot of repression or constraints on democracy like in Cambodia, but at the same time, the Internet right now is actually where everything is happening. It’s also mostly free; Facebook and Google are still accessible, Twitter is accessible. So if we don’t work to protect the space, this is going to have a huge impact on democracy and freedom of expression in the region. It’s going to be a battleground for democracy.”

Thanks to Casey Tilton for editing and guidance.

Dan Bateyko is Internet Monitor’s research assistant, supporting the team’s work researching Internet censorship and content controls. You can find more of his writing at https://dbateyko.me .