The Saudi Cables beyond the Saudi Cables: How to Assess the Impact

Last week, Wikileaks released the first 60,000+ of a reportedly more than 500,000 internal cables from the Saudi Arabian Foreign Ministry. These documents have generated tweets and news reports about Saudi government spending, internal government deliberations about regional policy issues, and details of lavish, private spending by the royal family.

Does the release of the Saudi cables matter? As the response of the Saudi government to citizen sharing and spreading of these documents unfolds and the contents of the remaining cables are revealed, by what measure might we assess the potential of these documents to impact the Saudi Arabian political landscape?

In the early days of Wikileaks’s rise to prominence, Wikileaks founder Julian Assange himself has discussed the organization’s mass publication of non-public government documents not as an end in itself but as a potential means by which others can challenge power. In a 2006 essay, Assange explains this as follows:

We must develop a way of thinking about this structure [of bad governance] that is strong enough to carry us through the mire of competing political moralities and into a position of clarity. Most importantly, we must use these insights to inspire within us and others a course of ennobling and effective action to replace the structures that lead to bad governance with something better.

In a 2010 Democracy Now! interview, Assange articulates on an operational level what he thinks is the purpose of publishing documents as part of a larger attempt to affect change, as follows:

…It’s not just us exposing abuses of war, it’s not just us exposing corruption in Africa; rather, it is insiders who are men or women of good conscience who are deciding to help expose the situation, because they want their own organizations to be reformed.

Together, these two characterizations of Wikileaks’s aim suggest that Assange means for the release of documents to go hand in hand with broader, local motivations for change and that the publication of leaked documents can help bring this about. It is what Saroj Giri, lecturer in Political Science at the University of Delhi, described as “Wikileaks beyond Wikileaks,” or the capacity of the leaks to affect “the widening of the fight and the struggle carrying in newer ways,” where Cablegate alone was relatively inconsequential. Likewise, philosopher and cultural critic Slavoj Zizek argues that while Wikileaks in and of itself may not provide unexpected or surprising information, it “[changes] the very rules” for “how…to violate the rules.” In this way, Wikileaks’ publication of secret documents is thought potentially to be generative in and of itself of new channels for questioning and transforming institutions of governance.

In the case of Saudi Arabia, then, where the structural conditions surrounding the cables may be less conducive to the response of citizens, is the replacement of “bad governance” with “something better,” in Assange’s words, a likely outcome of the kind of transparency Wikileaks claims to bring about? In The Oil Curse: How Petroleum Wealth Shapes the Development of Nations, Michael Ross argues that secret oil revenues allow oil-rich governments to “indefinitely provide more benefits than they collect in taxes” without citizens realizing this, which lets these governments “maintain popular support” (187). In turn, according to the oil curse theory, as long as the government provides benefits to citizens, they do not have to concede to popular demand to be transparent.

However, according to George Washington University political science professor and Middle East expert Marc Lynch, much more so than in the 2010 Cablegate leak – and contrary to Ross’s characterization of civil society in states associated with the oil curse – making sense of the Saudi cables has involved a distributed, participatory effort including both Twitter users and two independent media organizations, Mada Masr and Al Akhbar.

Furthermore, the documents are exposing information about government spending that Ross contends would be concealed by way of secret oil revenues (though perhaps not in a structured, systematic way) – for instance, government spending to back politicians in Yemen and government spending to bail out foreign television stations in exchange for more favorable coverage.

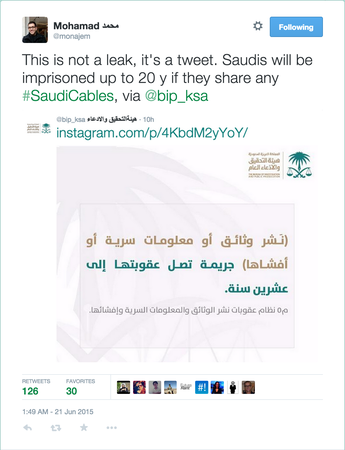

Amidst the use of #Saudigate hashtag, with which Twitter users have been tagging tweets linking to and commenting on particular released cables, the government has issued a warning indicating that publishing secret documents can result in 20 years in prison.

As the remainder of over 400,000 documents is released during the coming month, the question that remains is how grassroots and independent media efforts will fare in interpreting and publicizing the leaked documents.