Paid Trolls and Online Harassment: How a Journalist Confronts Azerbaijani Censorship

When she started writing about human rights and press freedom, Arzu Geybullayeva didn’t realize it would cause so much trouble. In fact, she didn’t intend to focus on these topics at all. When she started blogging in the 2000s, she was simply writing about what was happening in Azerbaijan. In 2008, Geybullayeva was one of only five bloggers posting in English in Azerbaijan. Soon, Geybullayeva and the few other bloggers became sources for embassies and other international organizations. Today, Geybullayeva is a journalist and fellow at the Berkman Klein Center and an Internet Controls Fellow with the Open Technology Fund, where she researches internet infrastructure and information controls in Azerbaijan.

Blogging led to her first professional writing gig as a columnist in 2009. “I never thought it would lead to exile. We joked about getting arrested, but we never thought it would really happen,” Geybullayeva said. In the past few years, the job has become more personal as she writes about her friends and tells their stories as they go in and out of jail.

She went on to write for Agos, an Armenian-Turkish newspaper in what she described as “conflict sensitive journalism” in light of the historic conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan. “I thought I would change mindsets; I truly believed in reconciliation,” Geybullayeva said. Instead, she remembers being labeled a traitor, a foreign agent, and being accused of selling state secrets to foreign governments. “Did I even know any secrets?” she joked.

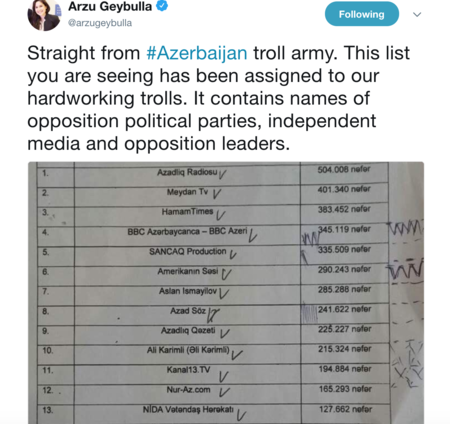

Tweet by Arzu Geybullayeva

While working at Agos in 2014, Geybullayeva received her first death threat. “That was the first time I really learned what defamation was on a personal level.” There were threats of rape, torture, and defamation through government media channels and social media. She remembers constant online harassment.

“If I was a man, they might not have openly come after my family,” Geybullayeva said. In Azerbaijani culture, mothers are revered and respected. In the days of the harassment and death threats, Geybullayeva remembers the threats against her mother as well.

Geybullayeva said it was difficult to open up about the online harassment and defamation she faced, but once she did she found many other female journalists who had experienced the same thing but had been afraid to talk about it. “We had a small but impressive movement of female journalists talking about online harassment...I learned that it's easy for journalists to feel isolated, so it is better to have a community.” Geybullayeva left Agos after over a year due to worries about her safety.

About five years ago, Geybullayeva was approached by Freedom House to write Internet freedom reports about Azerbaijan. Around this time, she noticed “more internet freedom problems, fishy amendments, and surveillance.” From there, she started writing about these problems and became involved with the international digital freedom community through Internet Freedom Festival in Valencia and Freedom Online Coalition meetings.

Information control, including Internet censorship, is not usually direct in Azerbaijan. Instead, the government relies on personal threats and self-censorship. There was a brief time around 2008 and 2009, according to Geybullayeva, when Facebook and blogging reached Azerbaijan but the government did not yet take them seriously as places of activism and organizing. As the rules started to change, activists and journalists were never charged explicitly with criticizing the government. They faced fraudulent drug charges or were accused of resisting authorities instead.

Geybullayeva says the biggest changes in persecuting bloggers and activists since then has been the severity of the charges, which now include tax evasion and “organizing mass disorder,” and prison sentences have increased from around two years to up to 10 years. Freedom House ranked Azerbaijan 45th out of 65 countries on Internet freedom. The government publicly recognizes five websites that are officially blocked for national security reasons, but Geybullayeva suspects that up to 40 may be closer to reality. Under current Azerbaijani law, the government can block any website “posing a danger to the state or society,” and a court must approve retroactively. “The authorities are very afraid of the Internet—they’re concerned with how much information gets out and how far it can reach.” She likens Facebook to a kitchen table for conversation, especially since the government crackdown on more traditional media.

Tweet by Arzu Geybullayeva

Beyond outright censorship, Azerbaijan’s government has taken to social media to promote propaganda and ideas from the ruling party. “The [Twitter] trolls are phenomenal” Geybullayeva said, describing the way that paid trolls take over conversations. “Some of them don’t know how to tweet properly. If you study their tweets they’ve been taken directly from statements from the president.” Based on her experiences and speaking with other activist and journalist colleagues, she observed that some trolls are assigned specific activists or members of civil society to troll. “They’re impossible to have a conversation with. They never listen, they just continue posting.”

Geybullayeva is not optimistic about the future of Internet freedom in Azerbaijan. People, especially in opposition political parties, are brought into the police station for posts, comments, and even likes. Many activists and journalists have been forced into exile like Geybullayeva, and others face travel bans or fear imprisonment or harassment if they speak out. “I have no immediate hope for the future of my country, not because people can’t mobilize, but because people are afraid to mobilize.”

Mary Meisenzahl is the Internet Monitor intern and student journalist at Wellesley College. Her work can be found at marymeisenzahl.com