Internet filtering hits home: Ethan Zuckerman’s blog blocked in UAE, Qatar, and Yemen

Guest post by Berkman research affiliate Helmi Noman

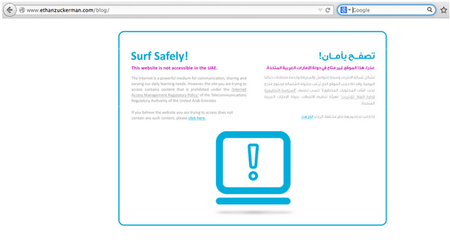

While trying to access MIT Center for Civic Media director Ethan Zuckerman’s blog today via the United Arab Emirates national ISP du, I encountered du’s standard blockpage.

I decided to test access to the website from Yemen, too, for two reasons: national ISP YemenNet uses the same commercial filtering solution as du, and its blockpage actually tells the user why a certain website is blocked. I found that Ethan’s blog is also blocked in Yemen; the blockpage says it is a “Web Proxy,” a content category that is targeted by censors in both countries.

I also had the blog tested from Qatar, which also uses the same filtering technology: the Canadian-made Netsweeper. (For an investigation of which countries use what technology to filter, see my 2011 paper with Jillian York: West Censoring East: The Use of Western Technologies by Middle East Censors, 2010-2011.) The blog was also blocked there.

I have been researching Internet filtering for years for the Berkman Center and Citizen Lab at the University of Toronto. I knew from previous filtering incidents to look into the provider of the filtering technology when there is no obvious reason why a national ISP has blocked a website. In a similar situation in 2011, tumblr.com and all blogs hosted by Tumblr were suddenly blocked in the UAE, Qatar, Yemen, and Kuwait, which surprised even the Internet regulator in Qatar. That was enough of a tip to have me look into the apparent suspect: Netsweeper, which provides filtering technology to all of these countries. I discovered that Netsweeper decided to categorize Tumblr and everything it hosts as pornography, a content category that is automatically blocked by the censors in these four countries.

It is not clear why Ethan’s blog was blocked by Netsweeper. But I take it from the Yemeni blockpage that Netsweeper miscategorized it as a Web Proxy. Ethan does discuss filtering and censorship, but his blog does not provide any direct assistance to users or tools for circumventing filtering. Using Google, I searched for the word “proxy” in Ethan’s blog and found that it was mentioned approximately 1,950 times. Maybe this is the reason why Netsweeper’s artificial intelligence, which scans websites for keywords for categorization purposes, flagged the blog. Whether this is the reason or not, Netsweeper owes Ethan, the research community, and the public an explanation.

Netsweeper used to make publicly available a tool that people could use to check how a certain URL is categorized on its database. That tool is no longer available, meaning the company’s filtering practices are now less transparent. The burden of finding out why a website is blocked is now on researchers. A company that sells its filtering technology to governments implementing Internet filtering on political and religious grounds should at least be transparent about how URLs are categorized. Other competitors, such as Mcafee SmartFilter, still offer this service to the public.

I think we are likely to see more of this type of filtering and miscategorization, especially because Netsweeper is selling its technology to more countries with questionable human rights records. Citizen Lab research has revealed that Netsweeper technology is being used to filter political and religious speech in more countries, including Pakistan and Somalia.

This filtering incident is yet another reminder that free speech on the Internet in the East is being restricted by technology made in the West; that these commercial filtering providers are not only used to block content, but also to decide by means of URL (mis)categorization which content should be accessible or not; and that the method of URL categorization is error-prone.