Human Computing and the Gamification of Surveillance Analysis

Recently unveiled surveillance blimp; courtesy of Raytheon, via Slate

Recently unveiled surveillance blimp; courtesy of Raytheon, via Slate

Since the US invasion of Afghanistan in 2001, the American military has worked to create a system of virtually continual real-time drone surveillance of the entire country. The system is not entirely automatic, however: in 2010, Marine Corps General James E. Cartwright noted that at least 19 analysts were needed to process video feeds from a single Predator drone. Looking through thousands of hours of collected video and audio recordings is particularly difficult. Cartwright described the work of analysis as sitting for hours watching "Death TV," searching for single or valid targets, an activity he called "a waste of manpower [and] inefficient."

To combat this inefficiency, researchers have experimented with building smarter cameras, capable of recognizing and reporting on suspicious activity, but the development of information gathering technology continues to far outpace the ability of computers to make sense of what has been collected. As an alternative, organizations have experimented with crowd sourcing the work of analysis to online volunteers; the US Air Force even asked ESPN for help looking through the footage. But what happens when the work becomes play, and the people involved don't know they're working as surveillance analysts?

courtesy of NASA

courtesy of NASA

In 2000, NASA began outsourcing the tedious job of identifying craters on the moon and Mars by encouraging pubic volunteers, nicknamed "clickworkers," to identify craters in photographs posted online. What would have taken a graduate student a year to accomplish was completed in only a week. In 2006, the state of Texas installed webcams along the Mexico border, streamed the feeds online, and encouraged the public to help monitor them for suspicious activities. One woman watching at 3:00 AM noticed someone signaling a pickup truck on the webcam and notified the police, which led to a high speed chase and the seizure of over 400 pounds of marijuana. Following the 2011 riots in London, police asked the public to look through thousands hours of CCTV footage and submit their own photos and videos to identify individuals who had participated in looting. Recently, a start-up in the UK began offering a service called "Internet Eyes," which connects the country's ubiquitous CCTVs to the Internet and offers the public rewards for identifying people committing crimes.

Important to note is that crowdsourced surveillance efforts don't necessarily lead to results: following the December 2012 shootings at Sandy Hook Elementary School, police asked for assistance from online crowds and were led to the wrong person. Following the April 2013 Boston Marathon bombings, a similar call for crowd assistance interfered with investigations and led to the wrongful accusation of several innocent people.

While many of these projects use crowdsourced volunteers to handle tasks computers are not able to do, the volunteers participating are typically aware of how their work is being used. These projects attract volunteers willing to give up a little of their time to help with a project they're interested in seeing succeed or help catch someone suspected of wrongdoing. In contrast, the next generation of surveillance analysis doesn't require volunteers to know who they're working for or even that they're working.

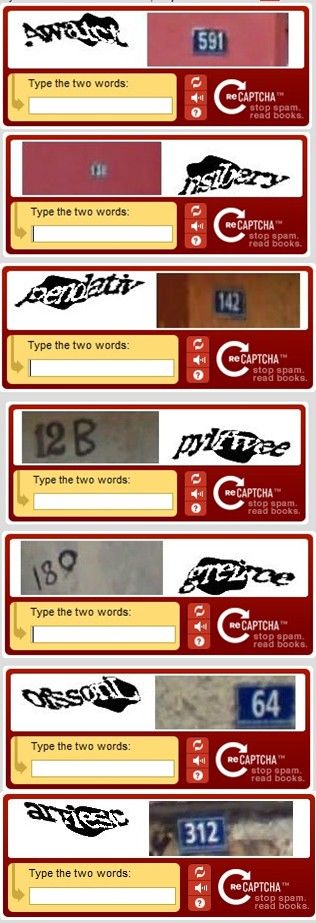

In order to tell the difference between human users and computer programs designed to spam websites, computer scientist Luis von Ahn created CAPTCHA, which presents users with a challenge-response test, usually a simple mathematical operation or an image of obscured text not readable by a computer, which a user must answer or interpret to proceed. Researchers associated with Project Gutenburg realized that CAPTCHA "had unwittingly created a system that was frittering away, in ten-second increments, millions of hours of a most precious resource: human brain cycles." They created a new system, reCAPTCHA, that could test for human users with images scanned from books that could not be read by a computer. Humans could decipher these scanned texts and, by entering them in as answers to the test, Project Gutenburg would be able to digitize enormous amounts of text. Since reCAPTCHA was acquired by Google in 2009, thousands of Google Books and nearly the entire archive of the New York Times have been digitized by millions of people who were not aware they were working for the project. In 2012, reCAPTCHA began using photographs of house numbers taken from Google's Street View project. Last month, the ACLU compiled a report that found that police departments across the US were using automatic license plate scanners to track and retain the movements of millions of Americans. The "automatic" scanners are often able to read and convert the images of license plates into computer-readable text on their own, but reCAPTCHA has also been used to digitize the more difficult images.

In order to tell the difference between human users and computer programs designed to spam websites, computer scientist Luis von Ahn created CAPTCHA, which presents users with a challenge-response test, usually a simple mathematical operation or an image of obscured text not readable by a computer, which a user must answer or interpret to proceed. Researchers associated with Project Gutenburg realized that CAPTCHA "had unwittingly created a system that was frittering away, in ten-second increments, millions of hours of a most precious resource: human brain cycles." They created a new system, reCAPTCHA, that could test for human users with images scanned from books that could not be read by a computer. Humans could decipher these scanned texts and, by entering them in as answers to the test, Project Gutenburg would be able to digitize enormous amounts of text. Since reCAPTCHA was acquired by Google in 2009, thousands of Google Books and nearly the entire archive of the New York Times have been digitized by millions of people who were not aware they were working for the project. In 2012, reCAPTCHA began using photographs of house numbers taken from Google's Street View project. Last month, the ACLU compiled a report that found that police departments across the US were using automatic license plate scanners to track and retain the movements of millions of Americans. The "automatic" scanners are often able to read and convert the images of license plates into computer-readable text on their own, but reCAPTCHA has also been used to digitize the more difficult images.

Luis von Ahn noticed how many hours people spent playing Windows Solitaire and devised an online game called "ESP" in which two players would be randomly shown a pair of images and asked to guess the word that best described the pair. When both players made the same guess, they would win points. Playing the game also contributed to building a database of labels for graphical search engines. Without even knowing it, millions of people playing an online game were helping to build surveillance databases and were working for free helping improve the ability for computers to search images.

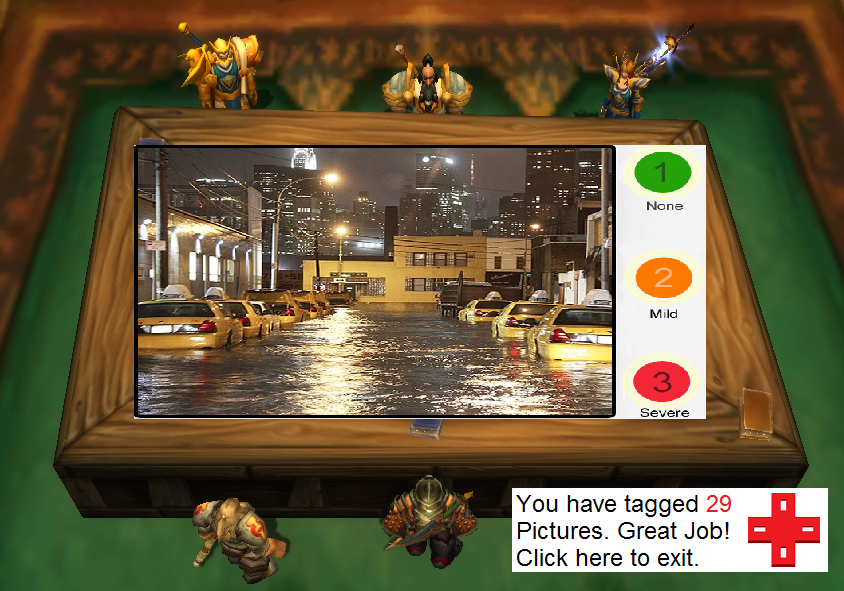

Big gaming companies and other groups are also taking note of the possibilities for "human computation" embedded in games. After researchers at the University of Washington led by David Baker successfully solved the puzzle of an AIDS-causing virus that had stumped scientists for 15 years in only ten days using an online game called Foldit in 2012, the gamification of tedious labor has been a popular concept. In early 2013, the Internet Response League launched a plugin that allows online gamers to help support disaster response operations. In Word of Warcraft, for example, gamers can receive disaster alerts and momentarily interrupt their play to tag images of disaster areas and rank them according to their severity. For the past four years, Ubisoft has been developing a new kind of game called Watch Dogs, set to be released in December 2013. As part of its marketing campaign for Watch Dogs, Ubisoft launched a website called WeareData that gathers and graphs real-world city data from London, Berlin, and Paris. Real-time data, including social network updates, the locations of Wi-Fi hotspots, and feeds from CCTV cameras, is streamed onto the site's 3D city maps. The actual game will also include these streams and is built to connect with players' Twitter, Flickr, Instagram, Facebook, and other social media accounts to provide seamless integration of these networks with game play.

Ubisoft's marketing website and eventual game highlights our visibility online (something we're already acutely aware of since the revelation of PRISM and other government data surveillance programs), but also suggests an alternative future of surveillance and analysis than the kind popularized by George Orwell's invention of Big Brother. It may not be long before someone like Luis von Ahn builds systems that rely upon the unwitting assistance of crowds to analyze CCTV feeds looking for criminals or someone like David Baker makes decrypting communications and files a fun game. Future players tagging photos in connected games like Watch Dogs might be helping to identify participants in riots while also collecting data on other players. People posting comments online, taking and tagging pictures for social networks, or simply drawing unlock patterns on their smartphone screens may help sort through the glut of gathered information. The surveillance analysts of the future may not be people wearing clipped on name badges watching hours of Death TV at the Pentagon. The work of watching and reporting may be done by all of us as we go about the everyday routines of digital life or escape for a while with a fun new game.