Clampdowns on Online Dissent in Modi’s India

Devu Chodankar, a 31 year-old resident of Goa, lived through the 2002 Gujarat pogrom. The pogrom, ignited by riots throughout the Indian state of Gujarat, was a three-day period during which nearly 1,000 people, the majority of them Muslim, died due to intercommunal violence.

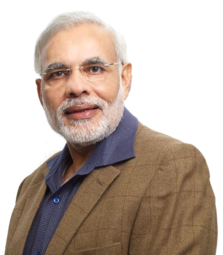

Narendra Modi, India’s freshly-elected Prime Minister, was Gujarat’s chief minister during this traumatic period in the state’s history; some accuse him of inciting the riots. In the run-up to India’s general elections in March, Chodankar posted on Facebook that he feared Modi’s potential victory would signal an “imminent threat of Holocaust as it happened in Gujarat” for Goa’s sizable Christian minority.

Prime Minister Narenda Modi, via Wikimedia Commons.

It’s a post that could land Chodankar in jail. Atul Pai Kane, vocal supporter of Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), got word of the Facebook post and reported it to Goan police. The police force’s cyber branch then transferred the case to the cyber crimes division. Kane claimed that Chodankar’s posts were aimed at inciting “communal disharmony,” insisting that he wasn’t targeting the posts simply because they were anti-BJP in nature. The post, Kane argued, was in violation of India’s Penal Code, which criminalizes the “promotion of enmity between different groups on grounds of religion, race, place of birth, residence, and language,” as well as the Information Technology Act, which punishes the distribution of messages that can be deemed offensive or false.

After being summoned to Goan courts twice in May, Chodankar was refused anticipatory bail. The Goan police have since been hunting Chodankar, who has since fled Goa to evade arrest, to investigate what was behind his comments—whether there truly was an attempt to disrupt communal and social harmony.

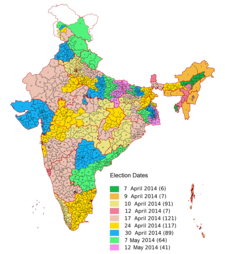

Map of India's 2014 General Election, via Wikimedia Commons.

Ritika Kayal, writing in Foreign Policy earlier this month, questions whether the political rhetoric espoused by Modi’s government accurately matches realities for netizens in the world’s biggest democracy. Distorted photos of Hindu warrior King Shivaji, likened to late Shiv Sena leader Bal Thackeray, were posted to Facebook last month; they have led to violent and intense citizen protests in Pune, resulting in the death of at least one person unconnected to the original Facebook post. In late May, five students who distributed a WhatsApp image of Modi’s fictional, imagined funeral were interrogated by police forces; one of the offending students was detained.

Kayal notes that Modi occupies something of a powerful, symbolic place within the Indian national imagination. Many Indian citizens see Modi as a more active go-getter who will orient India towards a more economically prosperous period, in contrast to his more passive and reticent predecessor Manmohan Singh. Observers like Kayal suspect that the overwhelming sense of national pride – one that has washed over the country since Modi’s election – may implicitly be creating a culture in which citizens are discouraged from speaking any sort of ill of their new leader.

Modi, who has championed free speech before, has remained silent on the incidents thus far, prompting criticism from media freedom and civil society activists in India, who in a statement released earlier this month called upon the Prime Minister to “respect the right of citizens' to express their thoughts and views, guaranteed by the Constitution of India, without fear of retribution.”